What is evidence-based design?

Evidence-based design (EBD) is the design of spaces based on evidence, not heuristics. The discipline of EBD was first developed in the healthcare industry. Its principles are now being applied across the built environment.

An important part of the design process has to be a real understanding of what the client is really trying to achieve and then develop some metrics and indicators to determine whether those objectives have been achieved.

What is important for the customer?

What is the starting point?

What is the end point?

How do we know that we’ve got there?

For example, is the client concerned about health and wellbeing, colleague engagement or productivity? These can all be measured, to an extent.

Some measurements may be physical or observational, e.g. how space is used. Other measurements might be associated with HR indicators such as absenteeism or complaints about the indoor air quality.

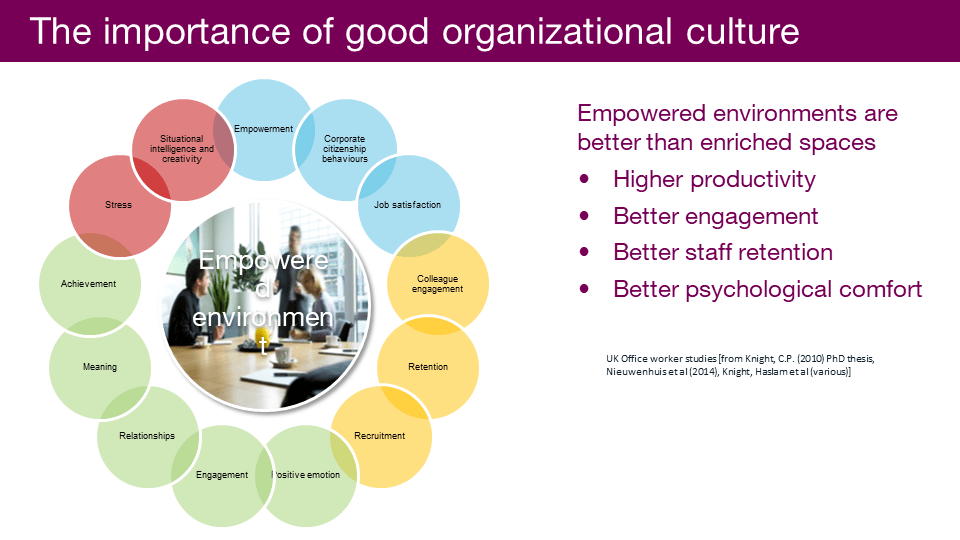

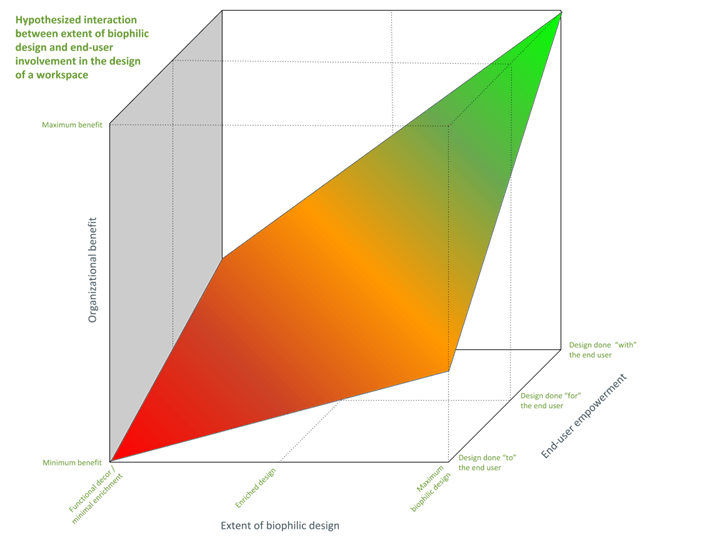

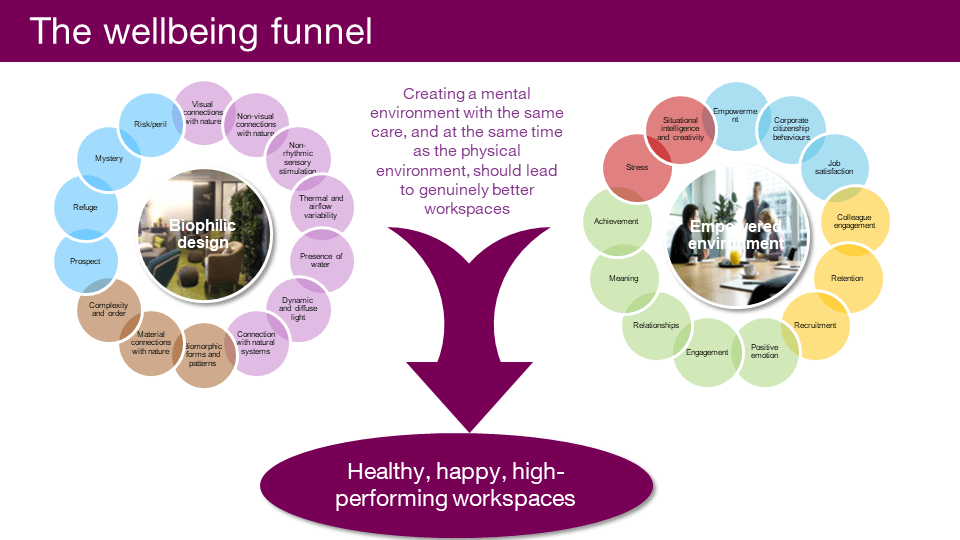

Maybe, the client is mainly interested in achieving a building certification (such as WELL) or a high Glassdoor rating in order to attract and retain staff. These may require a different set of metrics and, in some cases, might be achieved by ticking boxes and completing spreadsheets without needing to engage with the end-users of the space at all. Having said that, such a workplace, whilst meeting the specified end point of getting a certification, may not be especially effective. It is now well known that empowered, involved and engaged workers tend to be happier, healthier, more satisfied and more productive than those for whom a change was imposed.

However, without defining terms at the beginning of a project, the designer cannot really justify claims for its subsequent success. Objectives and KPIs must be clearly defined, otherwise the wrong metrics may be used, and without good evidence, it becomes impossible to know what tweaks might be needed once a new workplace design has been commissioned to keep it working effectively.

If EBD is applied without direct involvement from the end-users, the designer limits the amount and quality of evidence available.

Five-step approach to evidence-based guided design

I will illustrate the process using an example of creating an new interior landscape scheme in an office-based workplace, although the principles would apply to almost any types of design project.

Step 1: setting the intent and identifying needs

Here, the we state the intent of the exercise, seek to discover the needs of the client and identify any issues or areas that are important to the organization. These may relate to health and well being, productivity / financial indicators, staff engagement or even sustainability. Initial discussions would probably be with the client’s management team, but it would be wise to also engage informally with the premises users at this time and see if the management’s concerns align with those of their staff.

Outputs: KPIs agreed, scope and boundaries of surveys agreed, communications plan, workshops and end-user communications (e.g. newsletters)

Step 2: surveys and initial data

The next step would be to carry out a detailed set of surveys, including an assessment of the physical space (light, noise, layout, air quality, etc.) and a tailor-made staff survey, targeted at identifying and quantifying areas of concern.

The designer would also ensure that we have some objective baseline data from the client (if required) that could be compared against the designer’s own findings.

Outputs: initial surveys and data analysis, second staff communications, scope and boundaries of design agreed, design budget agreed.

Step 3: consultation and engagement

Before any intervention is made (for example, a redesign of the office space), the office staff should be kept engaged.

Research has demonstrated that giving office workers a genuine stake in the project (hearing their views and giving them real choices) results in better, and more durable, outcomes.

Throughout the process, the designer would ensure that all stakeholders in the project are kept informed of the progress of the project. This will be achieved using newsletters, social media and face-to-face discussions. At this point, the designer would have a fair idea of options available.

Outputs: ideas and requests collected from client’s staff, third staff communications

Step 4: design

At this point, an experienced design team would be brought in to discuss design options with all the stakeholders. Having reviewed all the initial survey information, they will have an idea of what might work and present some outline options to the client.

The designer would then take their collected ideas forward for discussion and engage all users of the office space in the final decision. Once this has been agreed, the design team would make arrangements for the space to be redesigned accordingly.

Throughout this process, it is important to keep all stakeholders informed. There is often a a few weeks lead time for a design to be installed, so the designer, and the client, need to keep everyone’s enthusiasm alive and build up to the day when their ideas are realized in their newly-designed work space.

Outputs: first design proposals for discussion by staff and management, revisions and final design choices, design specification and order, fourth (and possibly fifth) staff newsletter, design installation.

Step 5: Follow-up and continuous review

The client will need to know whether the interventions carried out in the offices have been successful, so a series of follow-up surveys (staff questionnaires, analysis of client’s data and physical measurements of the environment) could be carried out shortly after the new designs have been installed.

Such surveys might be repeated every 2 months or so for at least 9 months to confirm that the interventions have had a durable effect. If necessary, designs could be reviewed and adjusted as needed to satisfy the customer or end-users, as experience and use may highlight unforeseen needs.

Again, the designer would continue to communicate and engage with all stakeholders to let them know what is going on, and to get some qualitative evidence as well as quantitative data.

Outputs: follow-up surveys, data analysis, continuing staff newsletters

How will you know whether an environment is successful?

At each step of the process, data will be gathered to determine whether process is working. Data for evidence-based design can come from direct, indirect or proxy sources.

| Pre-intervention | At installation | Post intervention |

| Direct measures (examples) | ||

| End-user surveys End-user focus groups Sentiment / satisfaction measures Customer interviews Observational data Sensors and monitors | Discussions with end users – confirm needs have been met Discussions with customer – confirm needs have been met Sentiment / satisfaction measures | Ongoing Post intervention surveys (every few months for at least one year) Ongoing sentiment / satisfaction measures Interviews and focus groups Observational data Sensors and monitors |

| Indirect measures (examples) | ||

| WELL scorecard Fitwel scorecard RESET scorecard Sustainability scorecard Leesman index Revenue / person Revenue / square foot Absenteeism records Staff retention rates Review sites (e.g. Glassdoor, Trustpilot, etc.) | Absenteeism records Staff retention rates Review sites (e.g. Glassdoor, Trustpilot, etc.) | WELL scorecard Fitwel scorecard RESET scorecard Sustainability scorecard Leesman index Revenue / person Revenue / square foot Absenteeism records Staff retention rates Review sites (e.g. Glassdoor, Trustpilot, etc.) |

| Proxy measures (examples) | ||

| Tests and quizzes Simulations Comparison with similar organizations (impact seen with them probably similar to impact on us) Case studies References | Tests and quizzes Simulations Designer feedback | Tests and quizzes Simulations Comparison with similar organizations (impact seen with them probably similar to impact on us) |

Big Brother is watching you

Direct sources of data may be from automated systems and sensors. Sensors are increasingly being used to give building managers and space planners real-time data on how space is used and the environmental conditions in different parts of a building. This is becoming increasingly important now that hybrid ways of working are becoming more common and workplace usage patterns are changing rapidly.

Data collected on environmental and space utilization parameters allows for changes in layout or environmental management to be made rapidly, ensuring that users get as comfortable, and as useful, a workspace as possible.

Mapping survey data to culture, demographics and location: unveiling the nuances

While understanding the collective preferences of the end users of the workplace – the office workers – is crucial, digging deeper into the data and attempting to map these preferences onto the cultural, demographic, and locational peculiarities of the organization can give invaluable insights, revealing patterns and nuances that can be easily overlooked in broader surveys.

The benefits of longitudinal studies

Collecting survey data immediately before and after the installation of a new interior design is not especially valuable. People notice the immediate impact of change. However, tracking individual responses over time (whilst meticulously maintaining privacy), including for an extended period post-intervention, allows the designer to distinguish the subtle effects of design interventions from the larger waves of, say, a new CEO or a major business shift.

Granular analysis of data over time, ideally with the aid of a statistician, can offer a clear picture. It will reduce the risk of misinterpretations and helps to ensure that design decisions are informed by the most accurate trends.

Longitudinal studies, with frequent data analysis, also allow for post-design tweaks. Whilst easy-to-digest broad data can be appealing, the detail is where hidden gems of insight can be found.

Hidden gems

Demographic studies can hold surprising potential, as long as you know what to look for. For example, a seemingly innocuous study (carried out in the late 1990s) into the plant preferences of staff in a local government office revealed a hidden layer of cultural influence. The headline findings clearly showed a relationship between plant preference and the seniority of the office worker. Closer examination unearthed a deeper connection to gender, rooted in the organization’s history and norms: men occupied the bulk of the senior positions, whilst there were far more women occupying more junior roles. This highlights the importance of not solely relying on surface-level observations and instead delving into the details woven into the data.

Another small study challenged preconceived notions by demonstrating that job role, regardless of age, could be a stronger reflector of plant preferences than previously thought. Stereotypes, both reinforced and shattered, illustrate the power of data to illuminate the complexities of human behaviour within a specific context.

Ultimately, mapping data to culture, demographics, and location is not about finding definitive answers, but rather about uncovering the rich tapestry of influences that shape how people interact with their environment. By exploring the nuances found in data, evidence-based design transcends mere aesthetics and can be a tool that transforms workplaces into spaces that truly resonate with their users.

Measuring the right thing!

If the aim of a project is to improve employee wellbeing, then there is no point in measuring the organization’s Net Promoter Score. Likewise, measuring indoor air quality is unlikely to tell you much about a company’s brand reputation.

Having said that, there are likely to be some interesting interactions. Improving indoor air quality may well have an impact on productivity, especially if carbon dioxide levels are kept low, leading to greater alertness and less fatigue. However, you won’t know if productivity has been improved unless you actually measure it. Similarly, whilst improving employee wellbeing may lead to a better NPS score – happy staff are probably going to give better customer service after all – NPS isn’t, on its own, going to be a reliable measure of wellbeing.

Here are some possible aims of a design interventions with some of the metrics that could be used.

| Project aim | Possible metrics |

| Improved productivity | Revenue (or profit) per employee Revenue (or profit) per unit area of office space |

| Reduced absenteeism | Work days lost, long term absence, etc. |

| Increased office space utilization | Time spent in the office Workspace occupancy Sensor data |

| Improved wellbeing | Survey data: complaints of SBS, symptoms, reasons for absenteeism, etc. Health monitoring data |

| Improved environmental quality | Survey data: workplace comfort Physical data: temperature, RH, noise, VOCs, CO2 |

| Enhanced brand reputation | NPS data Ranking in reviews / indices (e.g. Glassdoor, Leesman, Trustpilot, etc.) |

| Improved colleague engagement | Staff engagement surveys, e.g. Q10, Hays Group, |

| Improved customer engagement | NPS Customer comments and complaints, reviews, etc. Customer satisfaction surveys Trip Advisor scores (for hospitality sector) Trustpilot scores (for service providers, retail, etc.) Increased footfall or dwell time (retail sector) Increase in return custom (retail, healthcare and hospitality) Customer referrals (retail, healthcare, hospitality) |

| Improved sustainability | GHG emissions normalized against revenue or per capita (rather than against floor space) Reductions in energy costs |

Add value to your interior design

If you are involved in design, especially if you are an interior landscaper looking to add value to your service, why not consider using an evidence-based approached to your designs? If you need help in putting together a programme or designing the surveys and other elements of data collection, then please get in touch.