Many modern office buildings incorporate ‘wellness’ rooms – places where office workers can go and decompress for a little while if stressed, overwhelmed or just in need of a few minutes of freedom from an annoying colleague or frustrating boss.

These spaces are often quite small, sited away from the main office space and often never used. They can allow HR departments to claim that they take employee wellbeing seriously and they might even result in a tick in box on wellbeing rating checklist or a favourable comment on Glassdoor, LinkedIn or a job board.

There are many reasons why they might not used.

- They can be hard to find

- They might be uncomfortable or poorly designed

- They might double up as places for other activities, such as prayer. This might make some people worry about breaking a taboo by using them for other purposes, or worry about when the room might not be available

- Their use might carry a stigma.

It is the last point that really needs addressing.

If someone is absent from their desk and their manager asks where they are, going to the wellness room can be seen as sign of weakness.

Or laziness.

When wellness rooms are nicknamed ‘Crying Rooms’, which I have come across, then it is clear that there is something wrong with the culture of the organization. When the privacy of a wellness room actually makes you more noticeable – because you are not where you are expected to be – then it isn’t really a private space.

So, what is the solution?

The most obvious solution is to ensure that the workplace is civilized. This means creating a corporate culture based on great leadership, trust and autonomy. Good corporate culture has the single biggest influence on psychological comfort and wellbeing.

However, even in organizations with great culture, there may be situations when one might need to retreat to a space like a wellness room to decompress, recover from overwhelm, physically relax or to meditate for a few minutes.

So, how can we ensure that such spaces actually foster wellbeing rather than just pay lip service to the concept?

It’s all about the senses

I have written before that biophilia is not just an airy-fairy concept, but is rooted in our evolutionary history. When we have a coherent sensory experience, we feel physically and psychologically more comfortable.

A wellness room needs to be able to satisfy as many, or as few, sensory needs as the user desires. These include:

Privacy

Your use of a wellness room should be absolutely private (with some caveats: for some people, the sound of a heavy door closing and locking can evoke memories of trauma).

You should not have to advertise your use of a space like this, whether by booking a time slot, seeking permission from a manager or even walking past a group of colleagues sitting near its location.

Furthermore, it must be completely enclosed and prevent any views in from inside the building. Solid doors and walls are essential, and the only windows should be to the outside world. Any windows to the outside should be clear. Some views can be relaxing and being able to focus on distant objects might relieve eye strain as well, but they must be capable of being obscured to prevent the user being seen if that is what is wanted.

Light, translucent materials, such as voile curtains would allow light in, whilst maintaining privacy. Their graceful, floaty form also provides some textural and visual interest.

Space

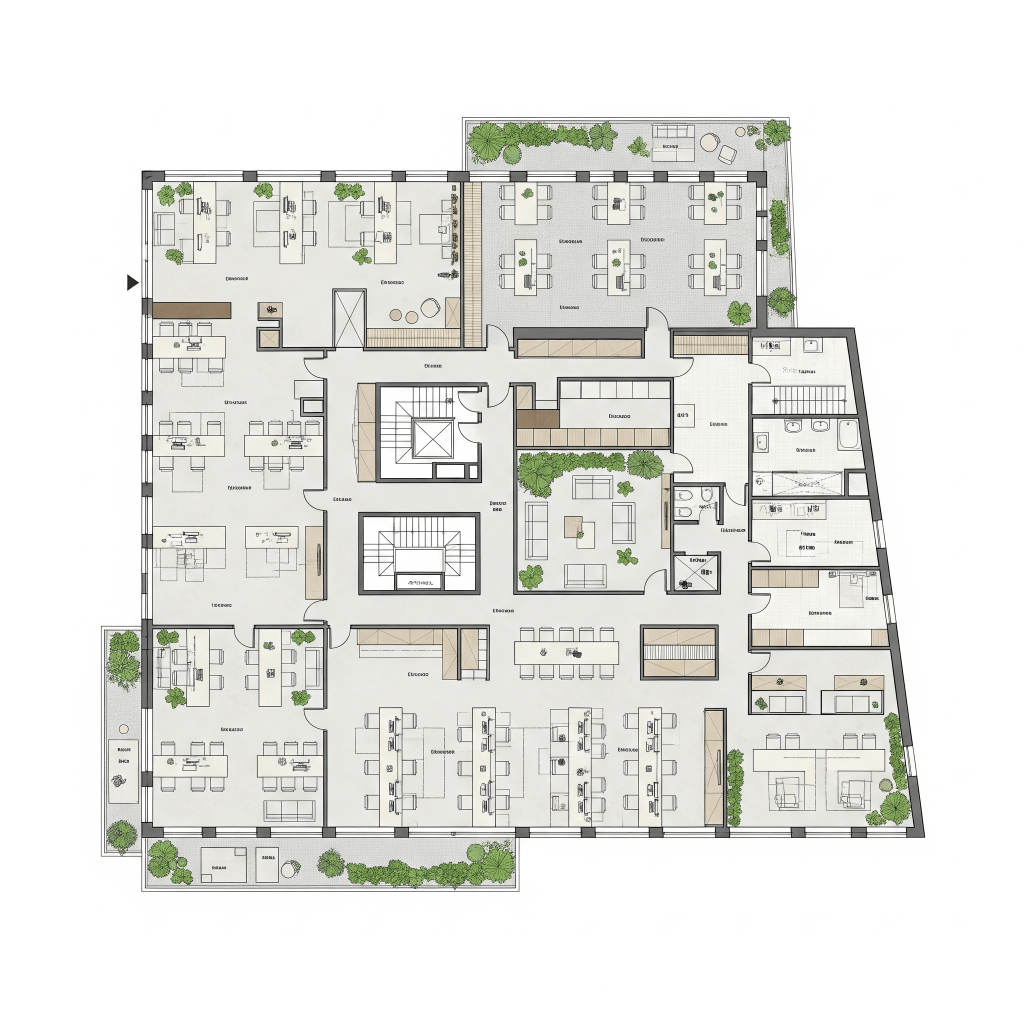

Wellness rooms are often small. They may have been converted from spaces such as small meeting rooms, a small private office or even a storeroom. This is understandable – floorspace can be very expensive, and must be productive. However, happy, healthy workers perform better and are likely to have greater job satisfaction. This means an investment in proper wellness rooms can make sense.

The space needs to be large enough to allow activities such as light exercise (such as yoga or other low impact activities), and also not be claustrophobic. The idea is to allow relaxation and decompression.

Some people may wish to lie down, so a clear floor area would be a good idea. There also needs to be space for a comfortable chair, or even a small sofa and maybe some other small items of furniture to give the room a lived-in feel.

Ceiling height should also be considered. Too low and you risk feeling cramped, or might not be able to stretch upwards. Too high, and it might lose the feeling of intimacy and cosiness that some might be seeking.

A wellness room with a floor area of approximately 3m X 4m would provide enough space to carry out light exercise, such as stretches or yoga, without being so big that it would compromise the feeling of shelter and cosiness.

Lighting

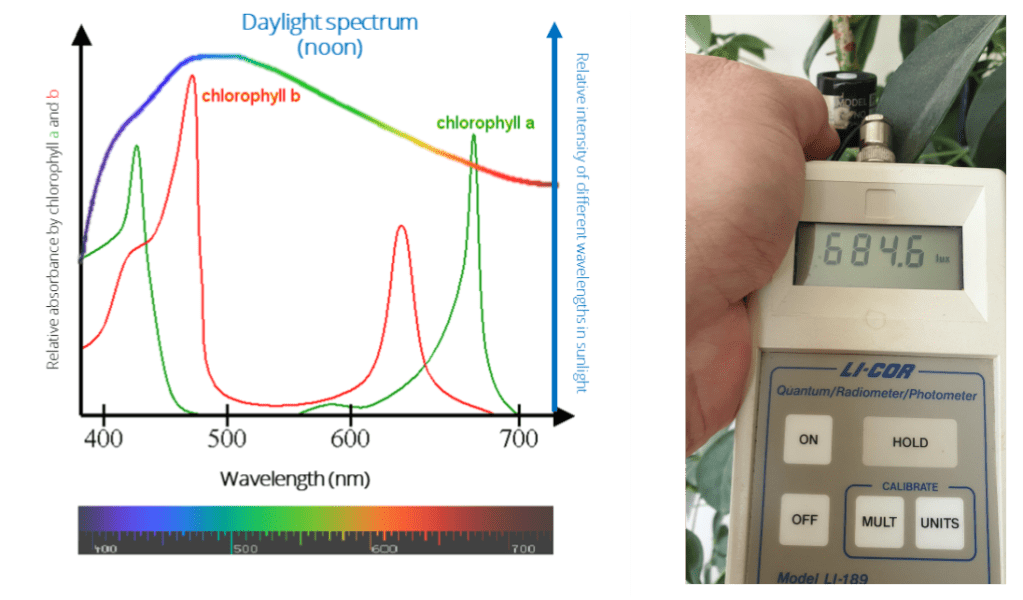

Light should be indirect and controllable – in terms of brightness and also quality. Lighting that includes far red / near infrared wavelengths are thought to have therapeutic benefits, and slightly warmer tones can be calming.

Placing luminaires so that they wash the walls and ceiling with light, rather than having a point source, will be more relaxing. The use of artificial skylights could also be considered.

Decorative lighting might also be considered. Whilst real flames would not be appropriate, simulated flames from LED candles, for example, can provide some non-rhythmic visual interest. Similarly, the placement of objects and foliage in front of light sources might cast some interesting shadows.

Sounds

Noise from outside should be prevented as far as is practicable, and noise generated from within the wellness room should not be audible outside. This has as much to do with privacy as annoyance and distractions.

Features such as soft furnishings, moss panels and even foliage plants can be effective at reducing noise levels.

Sound can be added to the space. They can be used creatively to mask outside noises or even simulate natural sounds such as water, wind in the trees or birdsong. There are many synthetic biophilic sounds available to play through a smart speaker or even download onto a smart phone. One of my favourites is Noises Online, which has 30 individual sounds that can be combined.

Smells

Ambient scenting systems are ideal to create subtle scent experiences. These are programmable and have a wide range of fragrances are available. However, care must be taken to ensure that the intensity of the scent is low – especially if the room is not used often and there are few air changes.

Reed diffusers are a cut-price way of filling a space with scent, but if the room is infrequently used, then the effect may be too intense, and cannot be ‘switched off’.

Neutral naturalistic fragrances are ideal. Bear in mind that some people are more sensitive to scents than others, so it must be possible to have a scent-free environment if possible.

Temperature control

This is likely to be quite difficult to manage – it depends on how the building’s environmental controls are operated and whether room-level control is possible. Radiant heat from underfloor heating is likely to be very comfortable for users of a wellness room – far better than warm air being blown around the space, which may result in uncomfortable draughts.

Having said that, sometimes gentle airflow, which mimics natural environments, can bring another non-rhythmic element into the space. A ceiling fan – which is controllable by the user – would be sensible addition to the space.

Textures

Textures offer both visible and tactile interest. A textured rug, made from fibres such as sisal or jute, can stimulate the touch sensors in bare feet, and features such as a moss panel, tree bark or even a small soapstone ornament can feel good in the hands. Having some tactile ornaments to handle, as well as surfaces, to touch can be very enriching.

Furniture and accessories

A wellness room should not be cluttered, and floor space should be kept clear, but it must feel like home. Well chosen furniture and accessories might include:

- A sofa or couch, possibly in a chaise longue style, to enable the user to sit or lie down

- A small table, where the user can place a drink. This could also be where some LED candles could be placed

- A large, soft, textured rug in the centre of the floor. Natural fibres, such as jute or sisal look very naturalistic and also have a nice texture

- Shelves or a wall-mounted cabinet where ornaments or books can be placed. This can also be where items such as towels or exercise mats can be stored or where bottled water can be kept

- Somewhere to hang clothes, place shoes and store bags out of the way

The nature connection

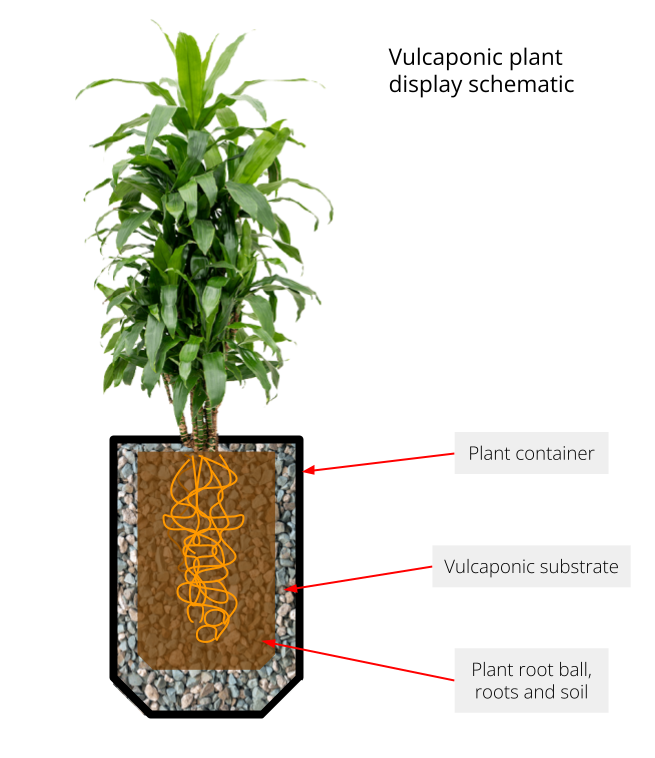

A selection of well-chosen interior plants would be essential. Plants that tolerate low light levels and intermittent lighting would be ideal. They should have a variety of forms, textures and shades of green.

A panel of preserved moss on one wall would also be ideal. These require little maintenance and have excellent acoustic and tactile benefits.

Indoor greenery, in all its forms, is my particular area of expertise, so get in touch for advice on this and for recommendations for a detailed specification and maintenance plan.

… and how to reduce sensory overload

For some people, especially some autistic people, sensory overload can be debilitating. The ability to access and make use of a quiet, calm, low-stimulus environment can be very helpful

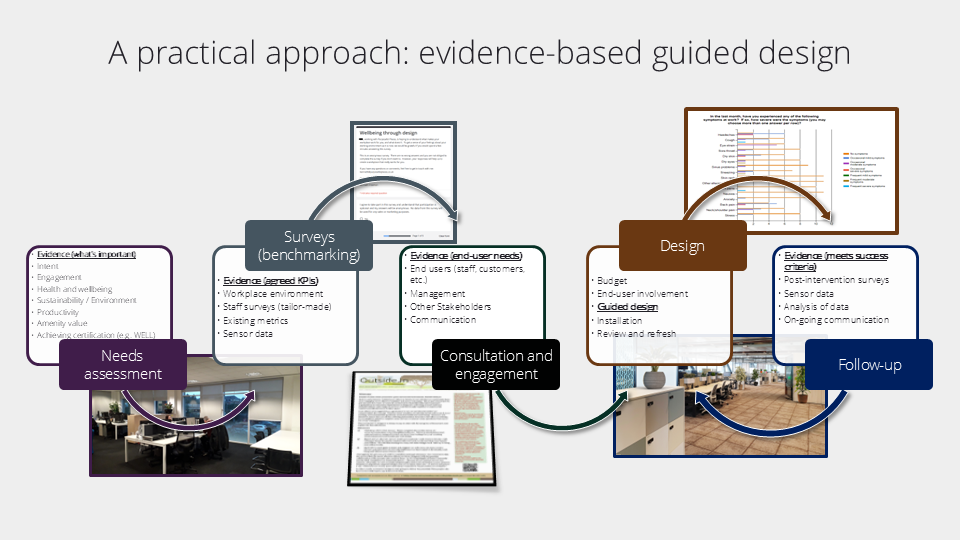

This means that control of the environment is essential. Being able to turn certain features on or off, or being able to do particular activities to suit individual needs is very important.

Provision for neurodiversity

The recently published design guidance: PAS 6463:2022 Design for the mind – Neurodiversity and the built environment provides excellent information for designers on how to create spaces that are accessible for individuals who may not be neurotypical.

Chapter 14: Safety, recovery and quiet spaces of the guide is especially relevant in the context of this article as it directly addresses the sensory environment.

The key takeaway is to give the user of the space as much control over it as possible, but where that is not possible, to design with hypersensitivity in mind – where spaces are as calming and quiet. It says…

Where only one quiet and restorative space or room is provided, it should be designed as a flexible environment with a variety of design options that are customizable to the individual’s sensory needs.

Each design aspect should have both low and high stimuli options to accommodate both hypersensitive and hyposensitive needs. In mainstream environments where only one space is provided, it should be designed as a low stimuli quiet space with higher stimuli optional additions by choice.

If multiple spaces are available, several spaces of various levels of stimuli should be taken into account.

When creating sensory or quiet spaces, the context of how the spaces are designed and the potential needs of the users should influence the design choices. If a facility is highly stimulating and busy, more than one space should be provided – quantity, quality and location should be taken into account.