February 2026 marked the 25th anniversary of the founding of Plants at Work – the UK trade association for the interior landscaping industry. The association represents dozens of firms that design, install and maintain plant displays in, on and around buildings.

Plants at Work members work in offices, shopping centres and hotels, looking after millions of plants. Among the wider horticulture industry, the sector is not especially well understood. Interior landscapers work indoors, not in the wet and snow. They don’t propagate plants, have no seasons to contend with and many of the horticultural techniques that are used are quite different.

In the UK, this sector employs thousands of well-paid horticulturists in companies that range in size from small family-owned firms to multi-national FTSE-100 companies. The industry turns over many hundreds of millions of pounds. Interior landscapers beautify the built environment and improve wellbeing, happiness and the profits and productivity of thousands of companies.

The origins of the association

Plants at Work was formed in a chilly village hall one evening in February 2001. It was the brainchild of Tony Sawyer, who is a supplier to the industry. He brought together a group of people from several interior landscaping companies – from the largest to small family-owned businesses. The reason was an outcry in the tabloid press about the maintenance of a large number of indoor trees at Portcullis House, the office building next to the Palace of Westminster where parliamentarians have their offices and the location of committee rooms.

As well as being very beautiful to look at, the trees were an integral part of its internal climate management system. However, “gotcha” journalists weren’t interested in their functionality, they were more interested in fomenting a scandal about tax-payer funded greenery.

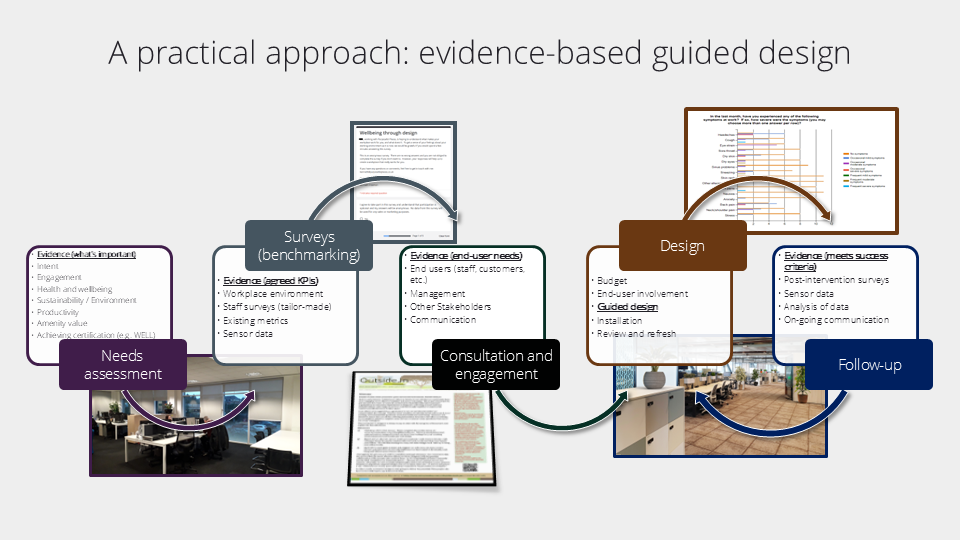

By 2001, there was already a growing body of research from all around the world demonstrating how plants in buildings improve wellbeing and productivity, and reduce stress. It makes sense to me that the people responsible for making the most difficult decisions on behalf of over 60 million citizens really ought to have a workplace that helped them make the right decisions.

Plants at Work (then named eFIG) decided to respond to the criticism as a group, and it used the collective power of the PR and marketing teams of its member companies to achieve this.

The need for coordinated training and best industry practices

Another driver to the association’s development was the lack of industry-wide best practices. Some companies had their own Research and Development departments (that was how I started in interior landscaping) and others had teams with decades of experience – often gained outside of the UK. Whilst a lot of that knowledge was proprietary, there was an identified need to have some common standards. This meant that clients could know that if they selected a member company, there would be some base-line levels of competence. This also meant that the association had to look at training.

Very few horticultural colleges cover indoor plants in their courses. Those that do often focus on propagation and the production of plants for the houseplant trade. However, houseplants are not necessarily the same as interior landscape plants. This means that training and education has to be the responsibility of interior landscapers, and this is where an industry association can really add value.

A need for greater visibility

One way in which an industry can gain credibility with its customers is to be seen. Awards events are a very good way of achieving this. Back in 2001, some interior landscapers were members of the BALI Interior Landscaping Group, and took part in their awards programme. The BALI awards are very prestigious and have a high profile, but the interior landscaping sector found it hard to gain visibility in the wider landscaping sector. A few years after our foundation, Plants at Work started its own awards programme. This gives visibility to, and recognition of, design and maintenance excellence, as well as the contributions of individual maintenance technicians.

Evolution of the industry over the last 25 years

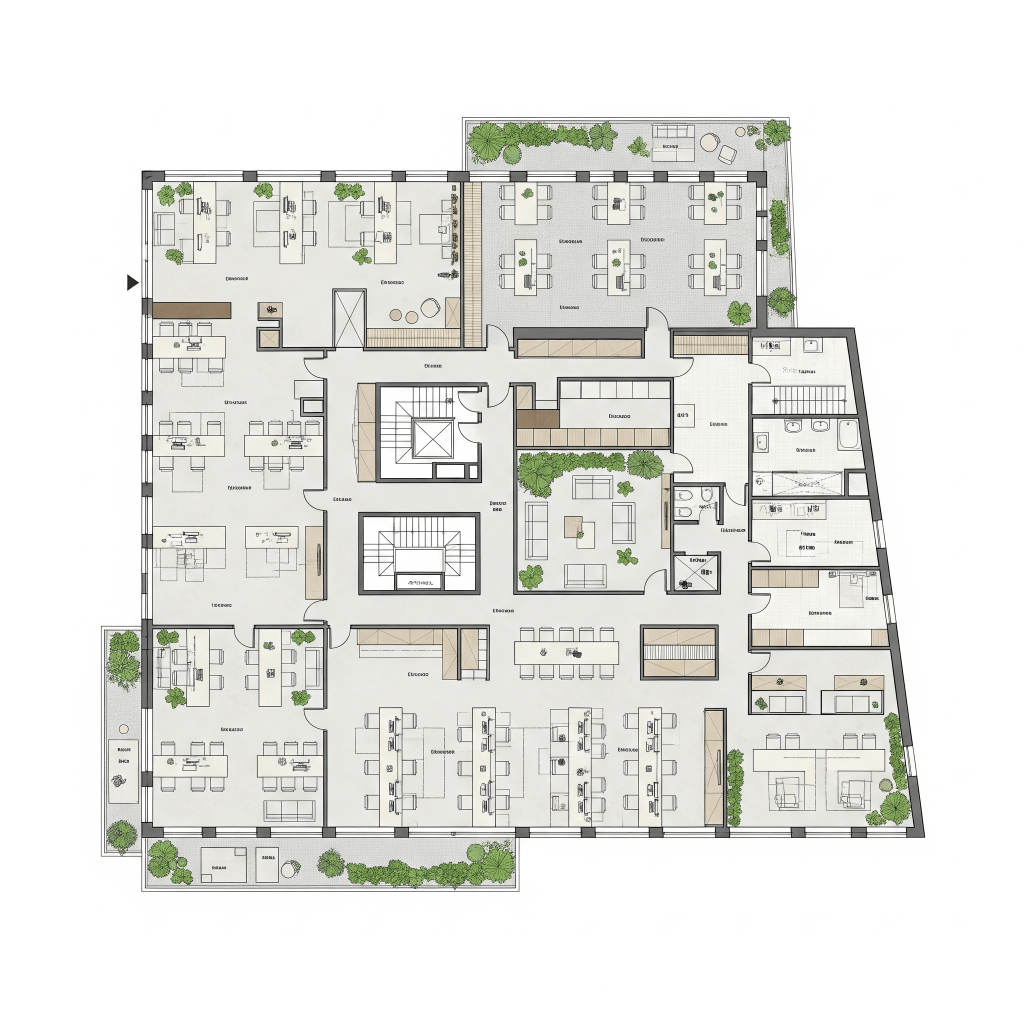

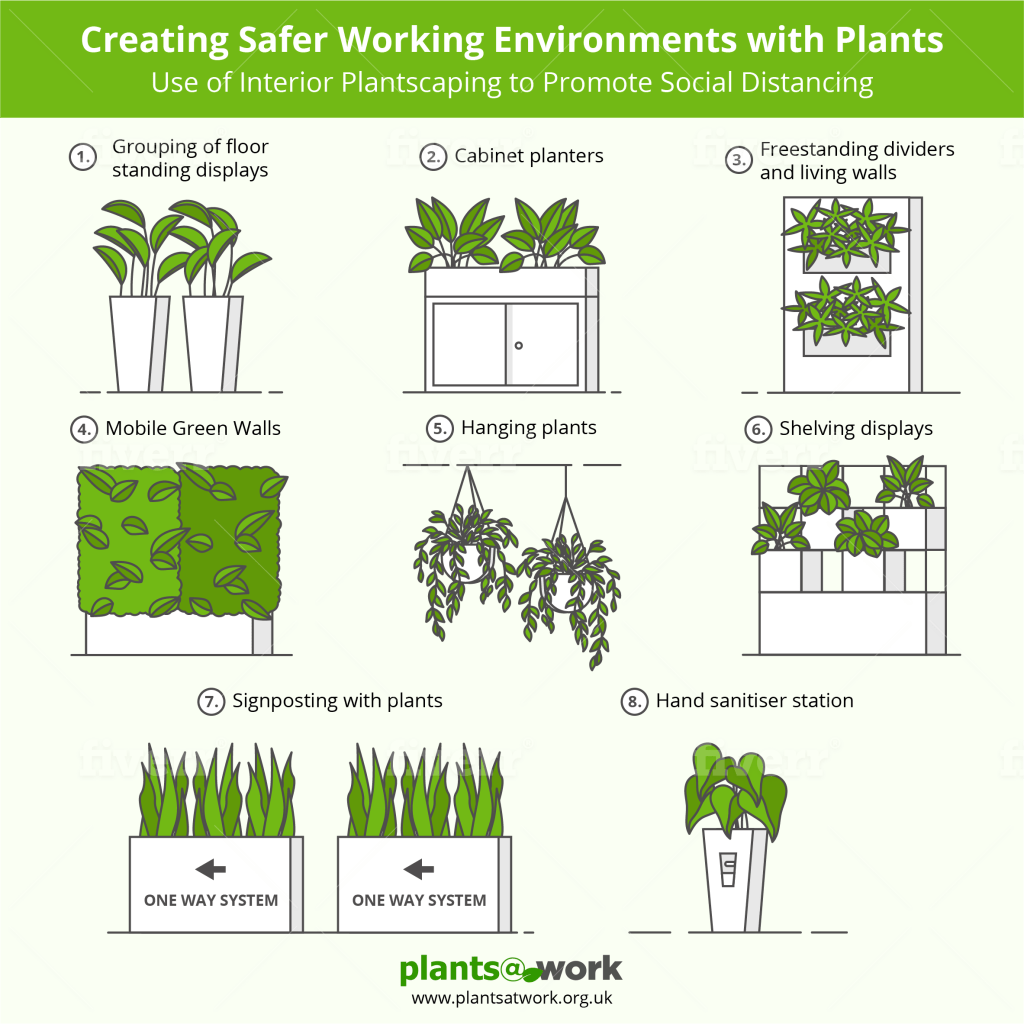

Interior landscaping is driven by two cycles. The first is design and fashions in interior design. These range from the minimalist, almost austere styles all the way through to interior jungles with vast amounts of tropical foliage. The cycle from minimalist to maximalist seems to be about 20 – 25 years. At the moment, interior landscaping is very popular and it is very unusual to find new, or refurbished, office buildings without abundant greenery. This has, no doubt, been amplified by the effects of the Covid pandemic and the drive to get people back to the office and make workplaces better. It seems as if a decade of office design evolution happened in eighteen months, and interior landscapers reacted quickly.

The other cycle is economic / political. During austerity, and especially following the financial crash in 2007, plants were seen as a luxury or a very visible item to cut from a budget. Despite the fact that academic research had shown that planted buildings could be as much as 15% more productive (making some pot plants more useful than some people), their removal could send a powerful message that the organisation was doing something to manage costs.

The attitudes that led to the complaints about Portcullis House (and that saga deserves an article all of its own) are resurfacing. For example, Kent County Council has just announced that they are cancelling their own interior landscaping contract for cost cutting reasons. I hope they do the sensible thing and measure the impact on their efficiency as a result, but evidence-based decision making seems thin on the ground.

Drive for sustainability

Another driver for our industry has been the need to improve sustainability. This is an area where we still have a lot of work to do.

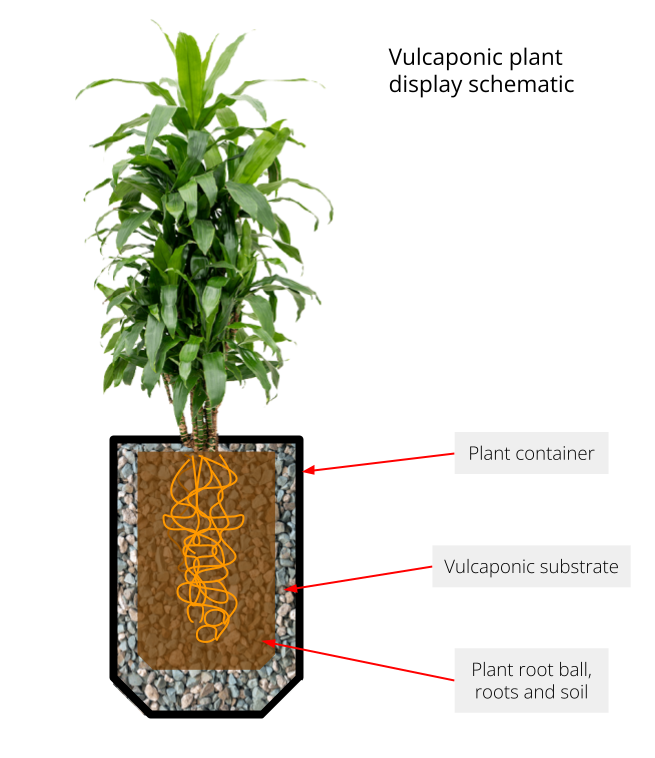

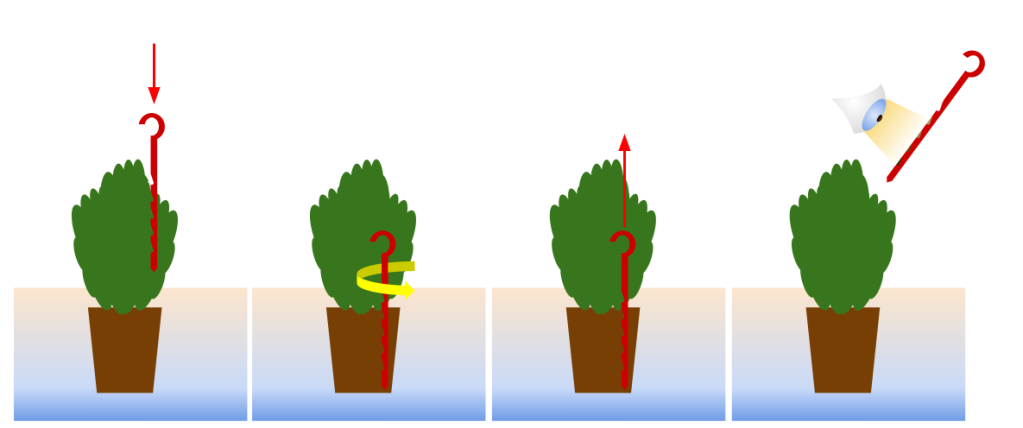

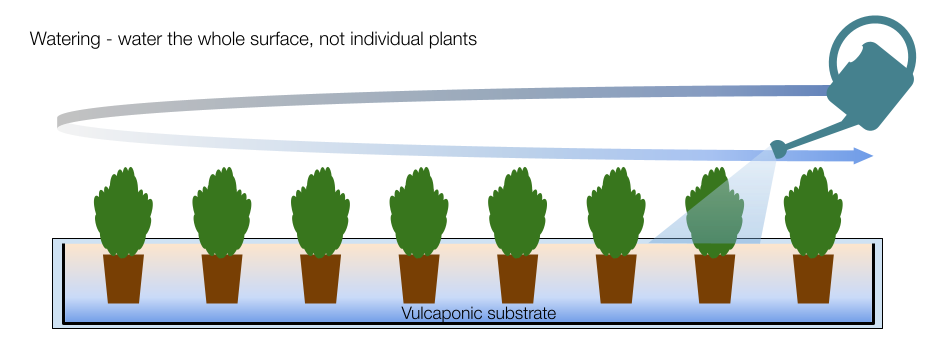

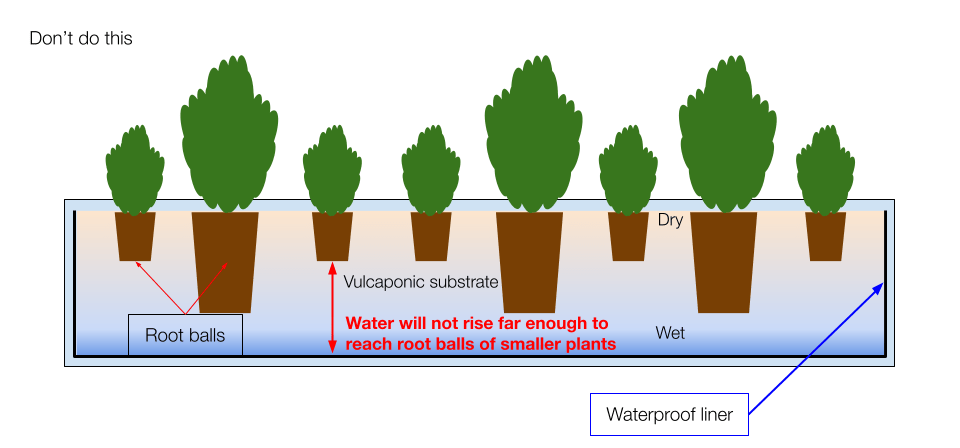

Many of our member companies have taken big steps to improve their environmental footprint. These are mainly focused on improving operational efficiency rather than anything horticultural. The electrification of vehicle fleets, the adoption of clever software to optimise service routes and the increasing use of sensor technology has made a big impact. However there are areas that we need to improve – water use for one.

Challenges we face as an industry

All sectors of horticulture face challenges, but ours might be a little unexpected for those working in other sectors. For example, we operate in an unusual regulatory environment.

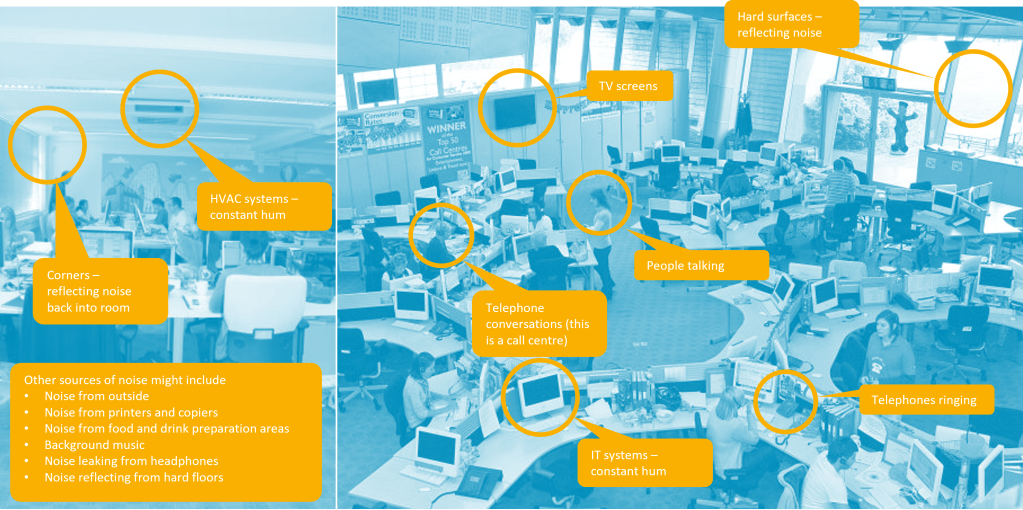

We look after plants in continuously-occupied buildings that are owned and managed by our clients. They are workplaces and the health and safety constraints are quite complex. Plant maintenance technicians have to do their work surrounded by office workers doing their job. They may be in buildings where security and confidentiality is paramount (banks, government buildings, etc.). They may need to gain access to high-level planting and must move discreetly between the desks in order to reach the plant displays without disturbing the staff in the office.

Interior landscapers also have to be very careful about the products they use to look after the plants. Even though pesticides are not permitted, other maintenance products need risk assessments that take into account the needs of the office workers (who won’t be wearing PPE) as well as the technicians.

Site risk assessments and task risk assessments also have to take into account the fact that work takes place in very close proximity to bystanders. Tools and products can do harm if not under constant control of the technician and, reasonably, some places are a bit squeamish about the use of long, sharp blades in their spaces.

Import controls and plant passporting

Another challenge relates to plant passporting. The rules are confusing and sometimes applied inconsistently. Getting the regulatory authorities to understand the complexities of ownership and control of plants is difficult. For example, rented plants are owned and maintained by the contractor, but are sited on a customer’s premises. Plants that are sold to customers under a guaranteed maintenance contract can be subject to removal and replacement. Mixed plant displays, often containing a dozen or more individual plants, might require the replacement of, say, a plant a month.

There are so many complexities in the supply chain and the subsequent use of the plants that record keeping is an administrative nightmare. Some definitive guidance would be welcomed, but it is difficult to pin down.

Bear in mind that 90%+ of interior landscape plants are imported (mainly from the Netherlands). The issues surrounding import control after Brexit have the potential to be really troubling. Fortunately, our suppliers are very used to exporting plants all over the world, not just within Europe, and they are adept at navigating these challenges.

Battle for talent

A good challenge to have is that the increasing popularity of interior plants displays means that business is buoyant for our members, and there is still growth. However, there is a real shortage of people wanting to work in the industry.

This is mainly due to lack of awareness – interior landscaping is a great sector to work in. We offer the opportunity to work in some of the most interesting and iconic buildings in the country, doing work that improves wellbeing and makes people happy. It pays reasonably well too. £30,000 pa is not an unusual starting salary for a plant care maintenance technician and there are good career progression opportunities. Sales people, designers and specifiers can earn even more.

What’s next for the industry? How we will develop over the next 25 years

The last 25 years have been interesting for the interior landscaping industry. We have seen many changes and I am certain we will see many more.

My crystal ball is a little cloudy. The nature of work – and consequently workplaces – will change, so there is no doubt that interior landscaping will be very different in 2051. I’m not sure that I’ll still be around to celebrate 50 years of Plants at Work, but I do think that our small sector of horticulture will be.

Traditional offices are likely to be less common. More people will use technology to work remotely and many office tasks may be carried out by AI and other technologies that have yet to be invented. However, people will still live in cities. They will need indoor environments that are beautiful, promote health and wellbeing and make a connection with our natural environment. Direct access to nature may be difficult, but greenery in, on and around buildings will be a vital component of our lives.

As an industry, we need to keep abreast of changes in the way buildings and cities develop as well as developing new horticultural techniques, products and services. That intersection of architecture, infrastructure, human behaviour and horticulture will provide interior landscapers with great opportunities to make the built environment a better place to be.