Biophilic design need not be confined to office buildings and other commercial spaces. The benefits of biophilic design can be obtained in the home office too, and without having to spend a fortune. This post explores the benefits of biophilic design and gives some very simple and cost-effective tips to help you thrive in your home working setting.

What is biophilic design?

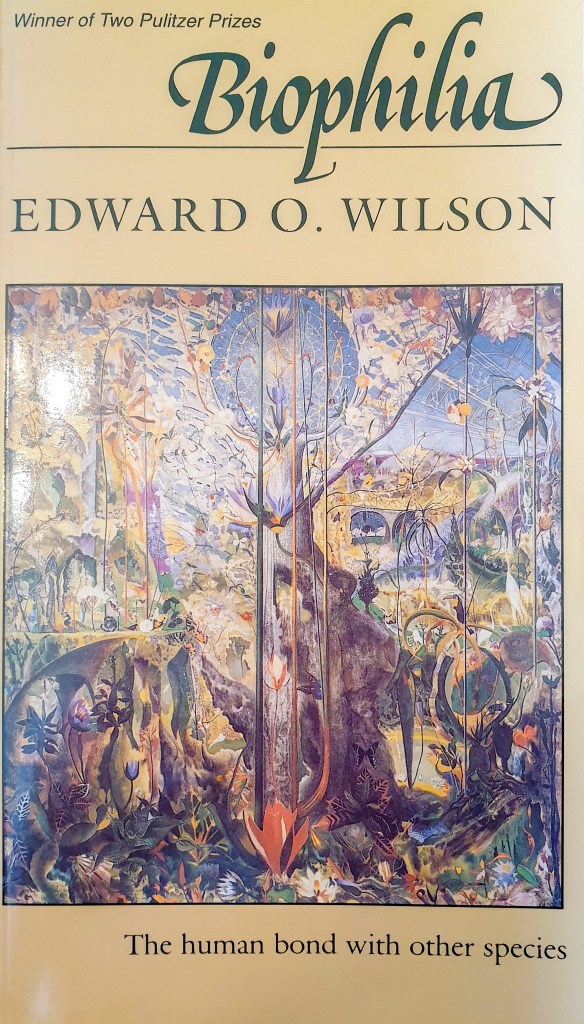

Biophilic design is a design process that brings the theory of biophilia into the built environment. Biophilia is a theory rooted in evolutionary biology and genetics, and was first popularized by Edward O Wilson in his classic book, Biophilia, published in 1984. Essentially, the theory reminds us that we are animals that have spent over 99% of our evolutionary history living in environments, such as the open plains of Africa. During that time, our survival as a species depended our senses being fine-tuned to that environment, and our reliance on various species of plant, animal and fungus for food, shelter and fuel.

It is only a few short centuries since we ceased being hunter-gatherers and domesticated ourselves to live in artificial environments, such as cities. In less than a thousand generations, we divorced ourselves from our natural environment and the sensory stimuli that we need to thrive.

Biophilic design is a way of creating environments that rebuild some of those sensory and biological connections, which reduce stress and increase wellbeing and happiness. Consider the domestic chicken. As a wild animal, the jungle fowl is a forest-dwelling bird that thrives by scrabbling around on the ground, picking up a varied diet of seeds, leaves, insects and other invertebrates. When domesticated and placed in conditions of intense population density and cramped conditions, they fail to thrive. However, the free-range hen, even though far from its jungle home, has an environment much closer to its natural conditions, and can lead a less stressful life, often living longer and requiring fewer veterinary interventions.

The battery human, also once released into a free-range environment (even though we are still constrained by our physical environment and societal expectations – hunting and gathering in the streets of our cities will be frowned upon) will thrive, and biophilic design is one way of creating such an environment.

The home office environment

The office worker has, in many instances, been let loose from the constraints of the office. During the pandemic, the cathedrals of capitalism were deserted and the shiny factories of data processing and document production went quiet. Even now, offices are significantly less occupied than they were before Covid-19 and, despite the frantic calls from the owners and managers of underused and expensive property assets, it looks likely that working from home, at least part time, will remain a normal part of working life.

As a result, the newly liberated office worker was forced to create a new working environment in their homes.

For some, this has been easy – there may be a spare room that can be used, or space at a large dining table, or even a garden building that can be used. However, for many, especially younger people living in expensive shared accommodation, creating a usable space has proved a challenge.

Good weather in the spring and summer gives opportunities to take breaks outdoors, whether in a garden, a public spark, or even a walk around the local streets. However, wet and cold autumn and winter weather means that the outdoors is a little less appealing. We need to consider how to create a working environment that maintains some of those connections with the outside world. So how do we do it?

Some simple tips for a biophilic home office

Give yourself a view

If possible, arrange your workspace so that when you look up from the keyboard or screen you can see out of a window. Even if the view is of another building, it will be something distant to focus on, and that will ease eye strain and bring give you a sense of what is going on outside – it might hello you decide whether to venture out on a break, or hunker down in the warm, but whatever the weather, you will connect to the world outside.

Open a window

An open window will refresh the air and flush out excess carbon dioxide and other pollutants generated from within the home. It will also bring the sounds of the outside world in – you may hear voices or birdsong or the sound of the wind. It might also be traffic noise, but even that can sometimes be a relief from silence.

Buy some houseplants

This is the eye-catching, Instagram-friendly intervention that will illustrate the pages of the colour supplements and lifestyle websites. However, it is an effective way of bringing some life indoors.

Houseplants need not be expensive or huge. Ikea, for example, has some terrific plants and pots at very good prices (and I am an expert on indoor plants, so you can trust my judgement on this). They add green interest to the indoor environment and also demand some care. Watering (not too much), cleaning and trimming and arranging plants can be very therapeutic.

Follow your nose

Our sense of smell is our most primitive – detecting chemicals in the environment (which is what the sense of smell is all about) was the first sense to evolve in the animal kingdom. We often react to scents instinctively and before we are consciously aware of them, so we can use fragrances to create a multi-dimensional sensory environment very easily. The range and quality of home fragrances is more comprehensive than ever before, so there is bound to be something appealing.

I’m not going to go down the road of recommending particular scents for particular settings or tasks – we risk straying into pseudoscience – just choose something that you, and your housemates, like.

Water

We use our sense of hearing and smell to detect the presence of water, often before we see it – this is a survival mechanism. As wild animals, we needed to be able to find safe water – not just to drink, but to find prey that also needed a drink.

The sound of rainfall or babbling streams can be found easily just by asking Alexa (or other smart speaker system). A fish tank or small indoor water feature can also be soothing.

Take care of your skin

The skin is your largest sense organ, but often the least stimulated in the working environment. As well as stopping your insides from falling out, your skin is home to sensors that detect temperature, pressure, movement and resistance, shape and texture and even changes in humidity and static electricity.

Don’t starve it of sensation. Use different textures around your workstation and allow your skin to be stimulated. Create a breeze (not a draught), experience some sunlight, walk barefoot, wear less if the temperature (or your need to be on a webcam) allows it or even take a shower for pleasure rather than utility.

Comfort is the key

Biophilic design isn’t just about plants. It isn’t about bringing nature indoors. It is about being comfortable – physically and mentally. Comfort brings happiness and happiness is the key to both life satisfaction and also job satisfaction. A little investment in comfort can pay huge dividends for the individual and employers relying on home-based workers.