Today is the 22nd of December, 2020. Here, in tier 4 Kent, it is quiet. Schools have broken up for the Christmas holidays and, thanks to a new strain of the Covid-19 virus, we are experiencing a near lockdown. This means the roads, and the skies, are nearly empty.

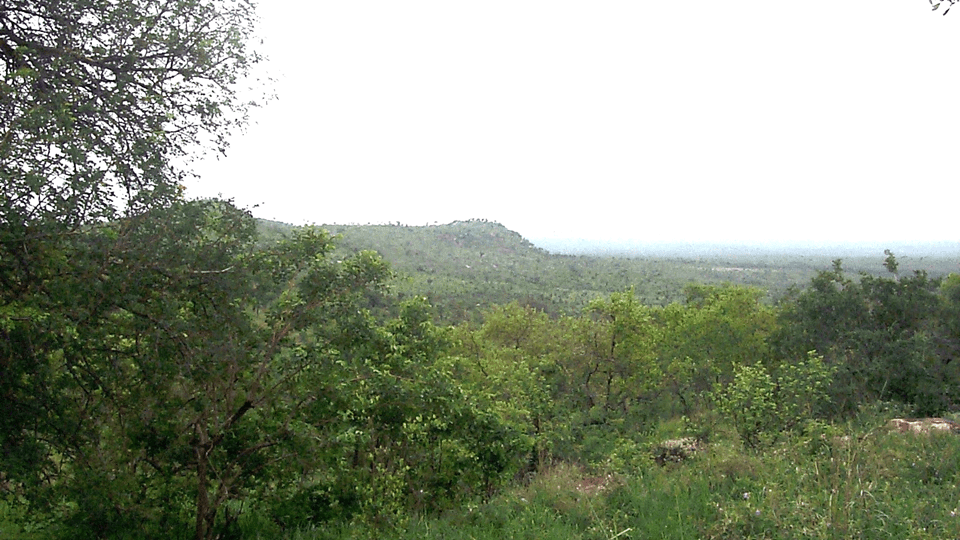

Oddly, it is also 14 degrees Celsius, the rain has stopped (for a while at any rate), and it is warm enough to sit in the garden with a cup of coffee and contemplate life. As I sat, looking at the garden (and thinking about the jobs that need to be done there, as well as those indoor chores, and for work), I tuned into the sounds. A robin was singing, pigeons and doves were making their less tuneful noises, and sparrows were chirping.

Around here, we also have small flocks of parakeets, which add an exotic touch to the area. Whilst they don’t have a pretty song, they do look stunning as they flash by.

That fifteen minute break cleared the mind in a way that a fifteen minute break on the sofa, or at the desk, couldn’t do. It allowed my eyes to focus on distant object (trying to find the tuneful robin in a holly tree), my sense of smell was treated to fresh coffee (which somehow smells better outside) mingled with the evergreen mossy smells of a damp garden and my ears tuned in to that bird. The sensory stimulation was congruent – there were no clashes.

A recent paper in Frontiers in Psychology (Minimum Time Dose in Nature to Positively Impact the Mental Health of College-Aged Students, and How to Measure It: A Scoping Review) investigated the research that has been carried out into how much time in nature is needed to positively impact the mental health of college-aged students.

It turns out that it isn’t very much. The authors sifted through over a thousand papers and carried out a detailed review of 14 of them. The key finding of the review was:

These studies show that, when contrasted with equal durations spent in urbanized settings, as little as 10 min of sitting or walking in a diverse array of natural settings significantly and positively impacted defined psychological and physiological markers of mental well-being for college-aged individuals.

Making yourself aware

One of the questions in the WorkFree assessment tool asks “When did you last hear birdsong?” It is not a trick question, it is there to make you think consciously about the last time you were aware of the sounds of nature. It is there to remind you to take as break from your desk once in a while and go outside and just be in the moment. Tune in to your surroundings and let your senses be stimulated from every direction.

This is even more important in the winter. It is too tempting to just stay indoors. For home workers, it could mean that you don’t even get a daily walk from your front door to the car or station (which office-based workers have to do, regardless of the weather), and that means your world shrinks to a few square metres.

Being in nature does not necessarily mean being in the countryside

The study mentioned above refers to how much time in nature is needed to benefit mental health. The studies excluded long excursions into deep wilderness (which is just as well, given the scarcity of real wilderness in Southeast England) and concentrated on easily accessible nature. That means public parks and gardens as well as walks in the countryside, and almost everyone in the UK is within a few minutes walk of a public open green space, whether it is a pocket park, canal towpath or some woodland.

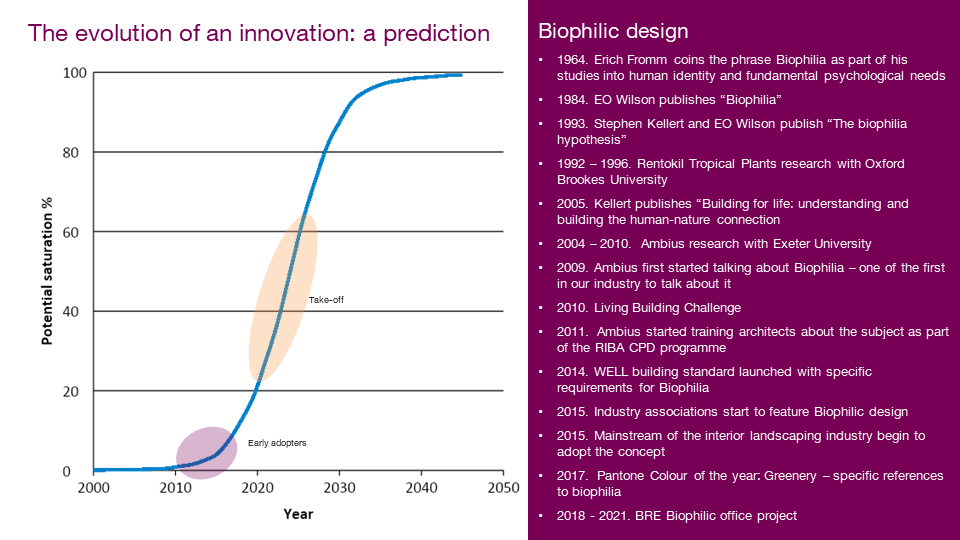

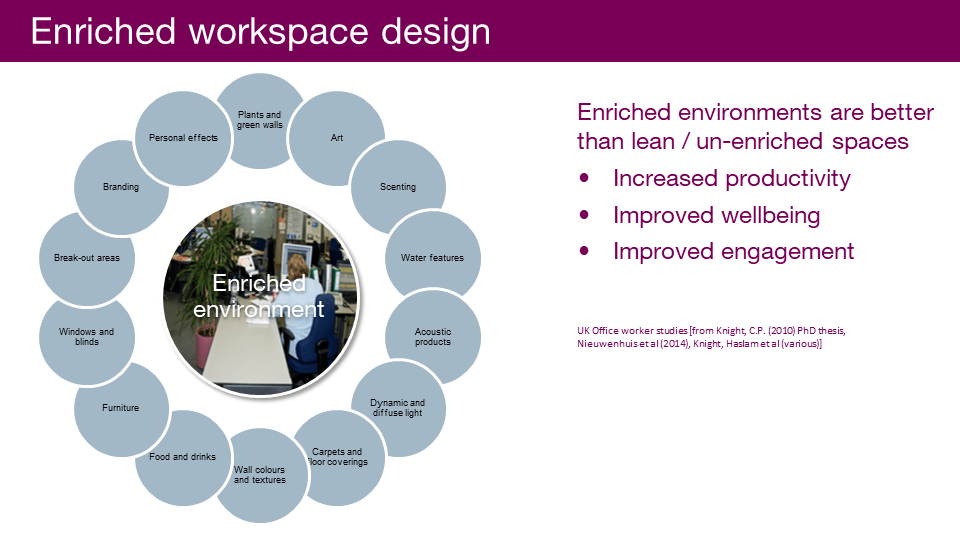

The benefits of being in nature, for even a brief period, are now well understood.

“The future belongs to the nature-smart – those individuals, families, businesses and political leaders who develop a deeper understanding of the transformative power of the natural world and who balance the virtual with the real. The more high-tech we become, the more nature we need”

Richard Louv

Richard Louv, in his book The Nature Principle, explains it really well. The whole book is very readable and I highly recommend it, but the chapters in the section called “Creating Everyday Eden” are especially relevant to the world of work, especially chapter 15, Nature Neurons go to Work. The book was written just as the benefits of biophilic workplace design were becoming understood – references to office design and indoor greenery abound, but the message is just as relevant now in times of home-based and hybrid working.