Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Did Isaac Newton contemplate the laws of gravity in meeting room 13N.21? No, of course not – he was famously in his garden in Lincolnshire.

What about Barnes Wallis? The idea of the Bouncing Bomb (of Dambusters fame) didn’t happen in a ‘collaboration zone’, but when skimming a stone across a lake. And Darwin didn’t come up with his theories of evolution in the confines of a meeting pod – his gardens at Down House, in Kent were his place of contemplation.

The poetry of Wordsworth wasn’t written as a result of sitting at a hot desk in a downtown office block, Hippocrates contemplated his theories of medicine sitting under a tree in the market place of Kos, and Archimedes had his eureka moment whilst having a bath.

There are innumerable examples of new ideas being inspired by something an inventor, philosopher, author or artist encountered outside of what we now regard as the workplace. Yet, if we were to believe the social media posts of commercial interior designers, or the marketing spin of companies boasting about how they have reimagined the workplace, you might think that we are entering a new golden age of discovery through the medium of office design.

We are certainly seeing more technology and a much wider range of space types inside office buildings (often supposedly to foster a sense of collaboration and creativity), and there is certainly a greater understanding of the principles and benefits (if not the application) of biophilic design.

The benefits of biophilic design in the workplace are becoming mainstream. The idea that bringing a sense of nature into our workplaces to support wellbeing and improve organizational outcomes is supported by a growing body of research, much of which has been referenced in some of my previous posts, and it is certainly true that you are more likely to be creative in a well designed, nature-inspired office space than in a sleek, bleak monochrome box.

It is interesting to note that in many businesses, there is a lot of ‘do as I say, not as I do’ attitudes from business leaders. As an office worker, you may be expected to be seen in the office and to make use of the investments made in design, but leadership ‘retreats’, often in nice country houses or rural resorts, are still common. They are justified on the grounds that such places, away from the distractions of the office (and annoying colleagues), are ideal for strategizing and creativity.

There are many good reasons why that might be true: I have written about why meeting rooms might not be so great for making important decisions because the elevated carbon dioxide levels found in such spaces can cause drowsiness and affect cognitive ability. Being away from distractions (or allowing yourself to be distracted by something divorced from normal work activities) is also great for thinking, and you never know where you might find inspiration. Being outdoors can certainly help – separating yourself from sources of stress and discomfort, and stimulating your senses by immersing yourself in fresh air and the sights, sounds and smells of nature can be inspiring.

Needless to say, hiring a resort is never going to be a cost effective solution to the needs of day-to-day creativity and imagination, but there are things you can do.

Human beings are a uniquely creative species, and we are able to gain inspiration from the most unexpected places. And whilst variety and a wide range of work settings now found in modern offices are to be welcomed (management permitting, of course), confining ourselves to one space for work isn’t going to be enough to unleash inspiration and creativity.

Even before the pandemic, the nature of office work was changing. There was an increasing shift to creating more purpose-based workspaces that accommodated different styles of activity, such as collaborative working or quiet focused work. This also led to an increase in the use of non-allocated desks (let alone private offices), so there was no guarantee, or expectation, that an office user would be at the same desk every hour of every day.

Then, the pandemic forced huge numbers of office workers to work from home, and many of them found it preferable. This has led to a rise in hybrid working, but has also acted as a catalyst for evolution of workplace design.

A decade’s-worth of change seems to have happened in about 18 months and many employers have completely remodelled their office space as a result: partly to attract workers back to the office by making them more comfortable and homely, and partly to adapt them to new ways of working.

However, with all the changes in workspace design, many offices are still less than half full for several days a week. A recent report quoted in The Guardian suggests that the Monday to Friday office occupancy rate across the UK is 29% for the first three months of 2023, and slightly less in London, compared with typical pre-pandemic levels of 60%-80% (according to data from Remit Consulting).

As a result of this, it is quite likely that suppliers of business-to-business (B2B) services are going to be impacted. Those companies selling discretionary B2B services, such as interior landscaping (my area of interest), are probably going to be especially exposed.

B2B companies that already have a nicely diverse mix of customers in terms of sector, size, and geography are probably going to be able to absorb some of the possible shocks, for reasons I’ll discuss later. However, those that are heavily dependent on one part of the marketplace, such as large corporate offices, might find themselves living in ‘interesting times.’ This is especially true where B2B service providers are not a directly-employed contractor, but appointed by a facilities management company.

The benefits of interior landscaping and workplace wellbeing are pretty much understood and accepted, so I don’t think there will be a large-scale chuck-out of plants as a cost-saving measure that we have seen in the past (such as the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis). However, if offices are only – on average – one third full, then it stands to reason that there will be a significant reduction in the floor space needed for organizations. Those empty floors won’t need plants, art, ambient scenting or coffee machines.

There is an upside for those businesses agile and imaginative to grasp the opportunities. Those office workers not commuting as often will still be working somewhere – and not necessarily at home. They will probably be spending more time working in places such as local co-working venues (several being set up in the suburbs and small satellite towns), coffee shops, or even in hotel lounges. All of these settings (often called third spaces) would certainly benefit from some nice plants – ideally supplied and maintained by a good interior landscaper. By offering their services to these spaces, interior landscapers can ensure that their plants continue to be seen and appreciated by workers, even if they are not based in a traditional office environment.

Even when the workforce is remote, employers still have a responsibility for the health, safety, and wellbeing of all their staff. It stands to reason that some of those discretionary B2B services could be reimagined as something to enhance wellbeing in the home working environment.

Many interior plant companies, especially those that have the infrastructure in place to deliver plant displays, could adapt quite quickly – some have already by offering mail order houseplants. Those companies could easily refine their offer by providing plants that are especially well suited to home working environments.

These could include plants that are easy to maintain (and maybe even be set up in such a way as to make plant care especially straightforward), and be properly matched to the home worker’s office environment. Advice and guidance on selecting the right plants for the space, together with instructions on plant care could be given, alongside tips on how to create a more effective home office space.

Workspaces are not as full as they used to be and hybrid and remote working is more common and more popular than ever before. Even with incentives (and demands) that people ‘return to the office’, there seems little evidence that office occupancy rates are getting back to pre-pandemic levels any time soon, or even ever. Indeed a recent report quoted in The Guardian suggests that the Monday to Friday office occupancy rate across the UK is 29% for 2023 to date, and slightly less in London, compared with typical pre-pandemic levels of 60%-80% (according to data from Remit Consulting).

Home workers have needs as well as office workers, and employers have a duty of care to their home-based colleagues as well as those in the office.

Here we discuss how the pandemic has accelerated the evolution of the workspace and why personal control over the working environment can benefit organizations and workers alike, especially when it comes to the air that we breathe.

Personal, portable air purifiers and monitors empower workers to maintain a healthy working environment, whether at home or in the office, and give reassurance to employers that they are fulfilling their obligations to ensure that their staff are safe while they are working.

Even before the pandemic, the nature of office work was changing. There was an increasing shift to creating more purpose-based workspaces that accommodated different styles of activity, such as collaborative working or quiet focused work. This also led to an increase in the use of non-allocated desks (let alone private offices), so there was no guarantee, or expectation, that an office user would be at the same desk every hour of every day.

The pandemic forced huge numbers of office workers to work from home, and many of them found it preferable. This has led to a rise in hybrid working, but has also acted as a catalyst for evolution of workplace design. A decade’s-worth of change seems to have happened in about 18 months and many employers have completely remodelled their office space as a result: partly to attract workers back to the office by making them more comfortable and homely, and partly to adapt them to new ways of working. However, with all the improvements in workspace design, many offices are still less than half full for several days a week and those workers that do go to the office are often scattered widely around the place.

Another element of our lives that has changed considerably over the last 10 years, and especially rapidly in the last five, is the use of technology to record aspects of our health and wellbeing. The first Apple watch was launched as recently as 2015 and, as well as being a smart timepiece, it can track many aspects of personal health and fitness. The data generated are available for detailed analysis and lifestyle changes can be encouraged.

Smart watches and smart fitness devices provide a minute-by-minute history of activity and health – including data about health whilst at work. These devices can be used to provide objective evidence of the health of employees in an organization.

And employers have an obligation to ensure that their employees are working in a safe and healthy environment – wherever they work.

Other smart, connected devices are also found in the workplace, providing valuable data in real time. These include occupancy sensors and, importantly for wellbeing as well as building management, environmental sensors such as air quality monitors.

The pandemic also increased awareness of indoor air quality, especially once it was recognized that Covid was transmitted in the air. Air monitoring is a useful tool here. For example, carbon dioxide concentration is a good proxy measurement of ventilation rate – the lower the CO2, the more the air is being refreshed from outside. Higher ventilation rates clearly result in the concentration of airborne pathogens being reduced. However, CO2 is not the only thing worth measuring – increasing ventilation might reduce CO2 and virus concentration, but it could mean bringing in other pollutants from outside, which also need to be measured and controlled.

Some recent research has shown a relationship between relative humidity, CO2, temperature and virus transmission – this has led to an interesting algorithm that has been deployed on some air monitors that gives an indication of Covid risk(1) (see this Whitepaper, published by RESET).

Alongside the development of health and wellness tracking devices, there has been a proliferation of voluntary standards designed to encourage and demonstrate how buildings impact the environment and the people that use them.

The WELL building standard is one of the best known. It rates a building’s ability to sustain and promote wellbeing across a wide range of parameters. Since launching in 2014, many thousands of buildings around the world have been certified. Other standards include Fitwel and the Living Building Challenge. A very useful comparison of 15 environmental and wellbeing standards can be found here.

However, these standards primarily relate to how a building works rather than how people work. There is an overlap, but the standards have not yet caught up with hybrid, or completely remote, ways of working.

How can we know whether our working environment is healthy?

When offices were predictably occupied, it was very easy to ensure that the working environment met legal and voluntary standards. The environment rarely changed and, if it did, it changed in a predictable and manageable way. Data were collected and facilities managers were able to control the environment of whole buildings from their computer.

This is still, of course, possible. But the control of whole buildings, or even fixed zones within buildings, is a bit of a blunt instrument when you don’t know where your employees are, when they will be in the building, or what they will be doing whilst they are there. At worst, it means making sure that the whole building is lighted, heated and air-conditioned just in case someone wants to use part of it. This is potentially wasteful of energy and resources.

Obviously, smart technology, such as occupancy sensors and light sensors can help, but even then, it is often the case that a large zone in a building is ‘switched on’ even if only 20% of the desks are occupied, and the occupiers of those desks scatter themselves as far and wide as possible.

In these cases, the building provides a safe working environment, even if the resources deployed are used inefficiently and expensively, but how can an organization discharge its health and safety obligations to remote workers – especially those that are new to remote working, or doing work that was previously wholly office based?

Over recent years, a lot of interesting research carried out in the UK and The Netherlands(2,3) has demonstrated that empowerment of the working environment yields huge benefits to workers and their employers.

Data can be very empowering. As discussed earlier, wearable technology and connected devices provide a huge amount of real time data about health and the environment.

Indoor air quality monitors can be very empowering. If they are visible and showing that there is something not quite right about the air, then the evidence required to make a complaint to the facilities help desk is provided.

As well as the office worker seeing the data, the facilities help desk should be able to see the same information. Not only that, but there will be a record of the data, so trends can be observed and potential problems identified and fixed quickly.

Sometimes, people are reluctant to complain, for fear of being regarded as moaners. However, a dispassionate air quality monitor can empower and embolden people to encourage their employers to manage the environment better, or even hand over control, where practical, to the users of the space concerned.

Where organizations are struggling to retain and recruit, such a visual demonstration of provision of a decent quality working environment is very helpful.

An air quality monitor might be one way to resolve arguments between facilities managers and building users – the decision to open a window can be validated by an improvement in the particular indoor air quality parameters that mattered to the user at the time.

This applies to home-based workers as well as those permanently in the office. Although the solution to the problem may not be in the hands of the facilities manager, it can still be facilitated by the employer.

Portable, personal air purifiers, such as Vitesy’s Eteria, offer employers and their staff the ability to manage one very important aspect of their working environment – the air they breathe.

It is a low power personal air purifier that creates a ‘bubble’ of cleaned air around the user, regardless of the size of the room. Instead of cleaning the air in the whole space, it is possible to optimize the quality of the air just where it is needed – around the person. Eteria uses information from the smart air quality monitor module to control the power of the purifier unit when it is connected.

Important indoor air pollutants can be removed or reduced below safety thresholds in approximately one hour, and the low air velocities means less noise. Low air velocities also means less air turbulence, which means that pollutants are not stirred up and spread around the room.

The air monitor component is very small, powered through a USB cable and is separate from the purifier. The purifier only works when connected to the monitor, but the monitor works all the time, providing data in real time and accessible through an app.

This means that it is possible to have a monitor on the desk at home as well as monitors on desks in the office – whether they are assigned workspaces or hot desks.

The purifier unit is very lightweight and can fit in a small bag or briefcase, making it easy to transport between home and the office.

(1) Raefer Wallis, Anjanette Green, Bela Nigudkar, Shichuan Xi, Stanton Wong. (2022) RESET Viral Index v1.1

(2) Knight, C., Postmes, T., & Haslam, S. A (2010). The Relative Merits of Lean, Enriched, and Empowered Offices: An Experimental Examination of the Impact of Workspace Management Strategies on Well-Being and Productivity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied Vol. 16, No. 2, 158–172

(3) Nieuwenhuis, M., Knight, C., Postmes, T., & Haslam, S. A. (2014, July 28). The Relative Benefits of Green Versus Lean Office Space: Three Field Experiments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied.

On the 8th March, Plants@Work (the UK trade association for the interior landscaping industry) was delighted to welcome Kali Hamerton-Stove of The Glasshouse to tell us about a project to help women ex-offenders back into employment through training, work experience and work placements in horticulture, especially interior landscaping and houseplant retail and mail order.

If you can spare half an hour, please watch the video of the presentation that Kali gave.

Having worked with The Glasshouse and some of the women in the project a few times, I can’t express enough how important this project is.

If you are a UK interior landscaper looking for new staff, please consider employing some of the Glasshouse alumni – they are trained in interior horticulture, highly motivated, have great personalities and have experience working in a wide variety of customer locations.

The Glasshouse’s interior current interior landscaping customers include businesses in financial services and hospitality.

The short answer to this is “often”. There is a lot of day-to-day variation, especially when the weather is quite active: a stiff breeze will disperse air pollution quite effectively. However, on average, most pollutants are at higher concentrations during the winter, and this is due to two main factors.

First, when it is cold we burn more fuel. These are fuels to warm our homes, such as gas or oil in a boiler, wood or coal on a fire, or fuels for power stations to generate electricity. All these combustion processes put pollutants, such as fine particulates and sulphur dioxide, into the atmosphere close to ground. We also burn more fuel in vehicles because the cold and wet weather makes walking and cycling a less attractive option for travel.

The other main factor is the weather. Often, we experience prolonged periods of cold, still weather. This is a result of high pressure systems that build up and trap pollutants close to the ground. This is especially pronounced in urban areas with high concentrations of people and traffic, but even in the countryside, pollution from home heating (especially wood burners) can become a local problem.

When you combine the generally poorer outdoor air, which will find its way indoors, with the greater amount of indoor activity that happens at this time of year, then it is pretty certain that indoor air quality will deteriorate unless you do something about it.

The atmosphere is composed of approximately 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, 0.9% argon and 0.1% of all other gases (including 0.04% carbon dioxide).

About 80% of the entire atmosphere is within 15km (10 miles) of the earth’s surface (which is only 0.2% of the earth’s diameter) – a fragile and wafer-thin envelope upon which all life depends.

The air that we breathe is made up of a mixture of gases, vapours and very tiny particles. Some of those components are essential for our survival (oxygen, being the most obvious example), most of the rest are harmless, but some can be troublesome, even in really low concentrations. Those troublesome components are what we would define as pollutants, and they are made up of particulates and a variety of chemicals (some of which are naturally-occurring). These pollutants can have an adverse impact on our health.

The amount of pollutants in the air that we breathe determines what we call air quality, and air quality can vary considerably from place to place and season to season and is influenced by weather, climate, volcanic activity and, most profoundly, by human activity.

The quality of indoor air is determined by the concentrations of a variety of components, and can be divided into those that are generated in the home and those that are brought in from the outside. They can also be divided according to their nature.

The most serious pollutants found in the home, and outside, are fine particulates. These are tiny particles, usually of soot emitted from vehicles and other combustion processes. They are between 2.5μm and 10μm in diameter and can be breathed deeply into the lungs, where they remain or break down – they don’t get coughed or sneezed out of our airways like dust and pollen. For comparison, human hair is typically between 50μm and 90μm in diameter.

Other pollutants that can affect our long-term health include a variety of volatile organic compounds, as well as other combustion products such as various oxides of nitrogen and sulphur.

Ozone produced and trapped in the lower atmosphere can also be harmful (when it is at the top of the atmosphere it provides vital protection against UV radiation).

Very many of the pollutants we find indoors are carried in from the outside – especially if you live in an urban environment or near a busy road. However, a lot are also generated within the home.

Cleaning products, room scenters and cosmetics all contain volatile organic compounds, as do alcoholic drinks and foods (if they didn’t, you wouldn’t be able to smell them). Additionally VOCs can be emitted from products such as adhesives, particle boards, paints and wood stains – and even Christmas trees. That fresh, piney smell is loaded with terpenes and other VOCs. Levels of many VOCs can be 5 to 10 times higher indoors than outdoors, and VOC concentrations of as little as 25mg/m3 have been found to induce airway inflammation and irritation.

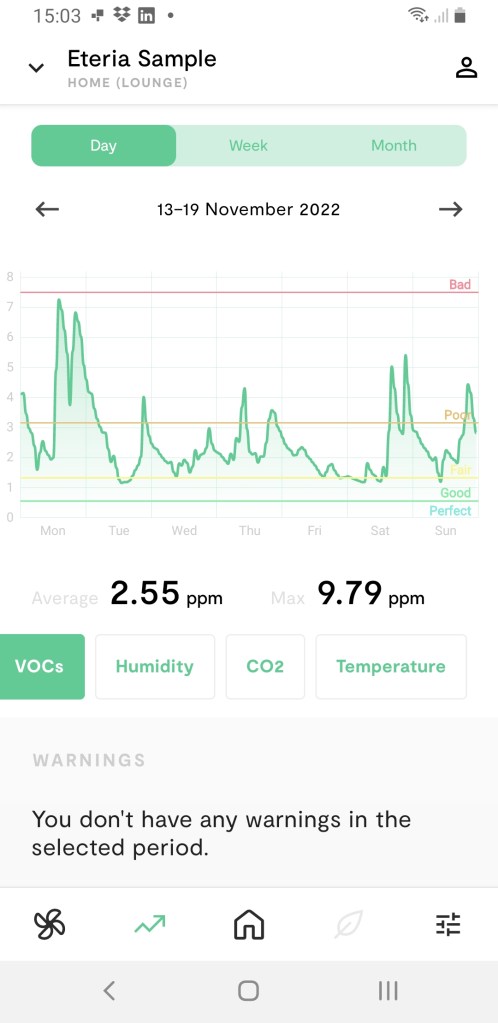

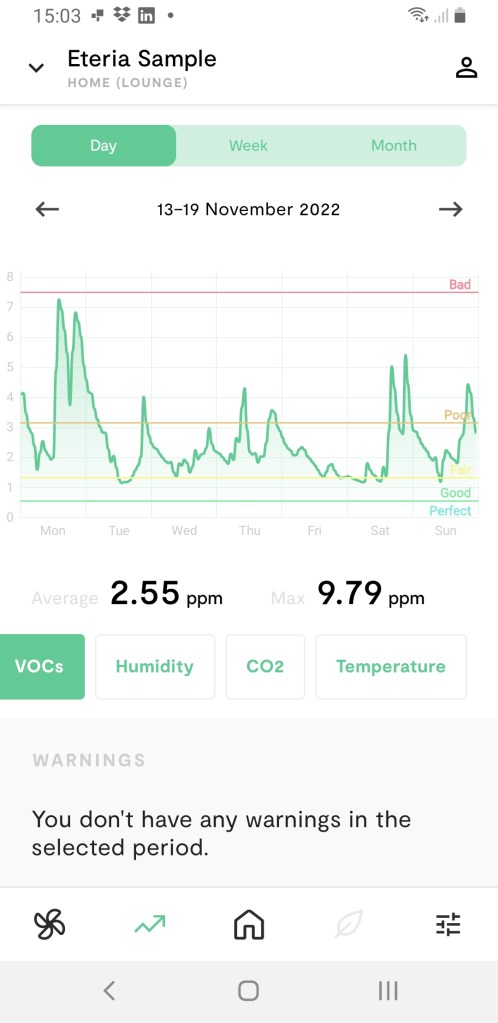

I’m very interested in seeing how indoor air quality changes in my home, and I have a couple of monitors that give me the information I want, including the monitor that comes with Vitesy’s Eteria air purifier. I am also a RESET accredited professional, the training for which gave me some very useful insights and knowledge.

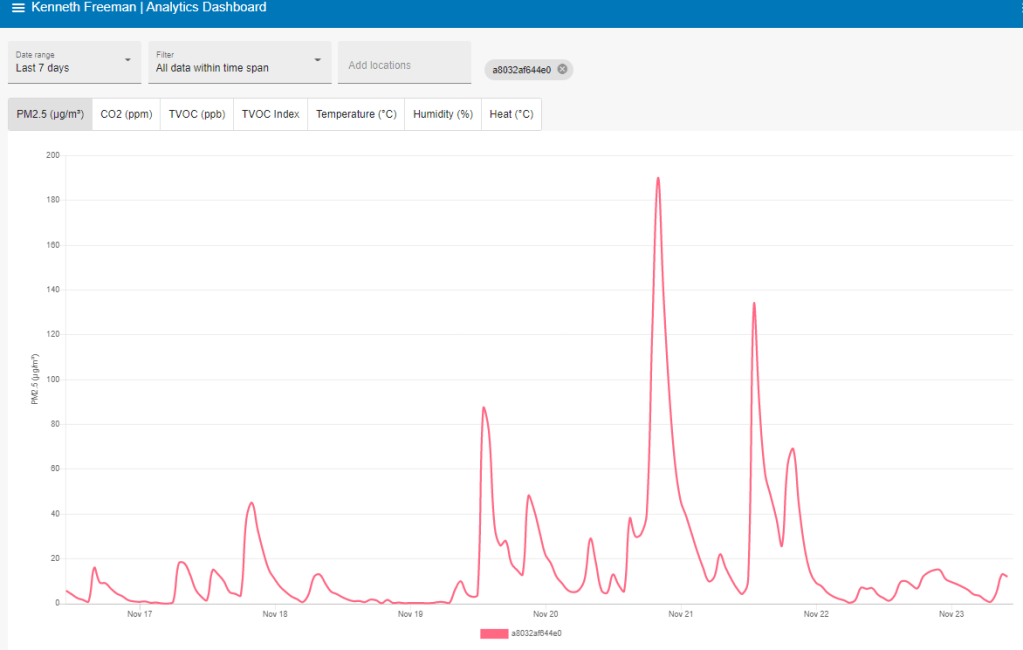

Here are the charts for my living room over a seven-day period in November 2022 (recorded on a professional-grade Air Gradient monitor):

The first chart shows the concentration of PM2.5 particulates. These are the fine particles that can be breathed deep into the lungs. There are some concerning spikes (although very short-lived) and I think that they correspond to the times when my log burner was first lit, before it started to burn most efficiently. In some indoor environments, high levels of particulates will be generated by smoking – second-hand tobacco smoke is a major contributor to poor respiratory health.

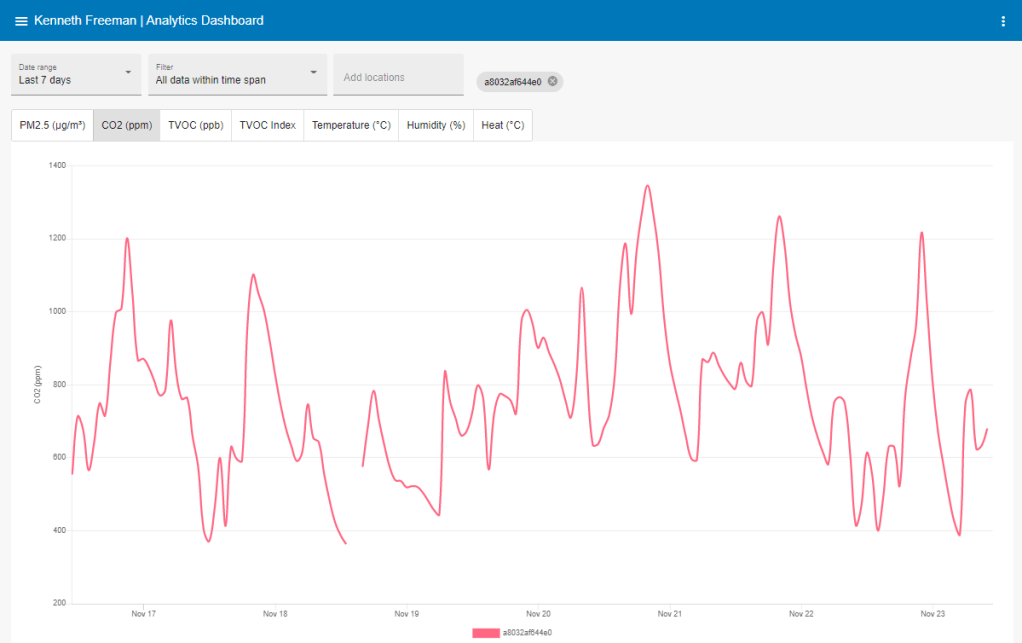

The middle trace relates to carbon dioxide. This is not, in itself, a serious pollutant, but is a very good proxy measurement for ventilation, and it also relates to the number of people in the room. There are some very good reasons for measuring carbon dioxide – especially in places like offices or schools, but less so in the home.

Recent research has shown that there is a relationship between carbon dioxide (as a proxy for ventilation), humidity, temperature and the risk of catching airborne viruses, such as SARS CoV-2 (Covid), and many air monitor manufacturers have incorporated an algorithm to give an indication of risk.

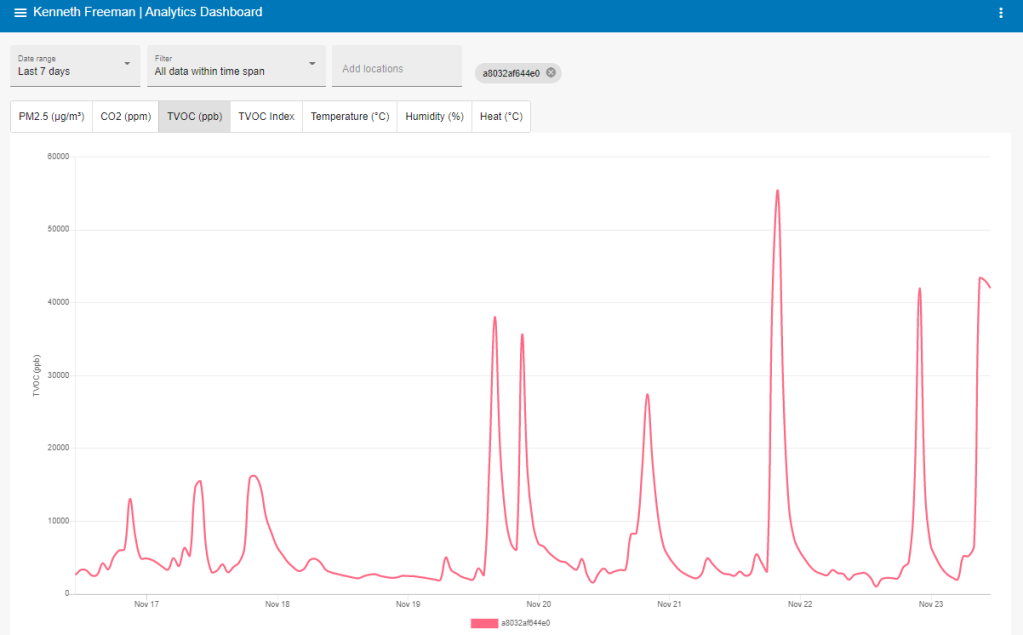

The next chart (below) is a record of total volatile compounds (tVOC). These can be generated in many ways and they spread around the air very quickly. In my case, I suspect that the spikes corresponded mainly to cooking.

Interestingly, on six occasions, VOC concentrations went above 25mg/m3, which is the level at which irritation and to the airways of sensitive people can occur.

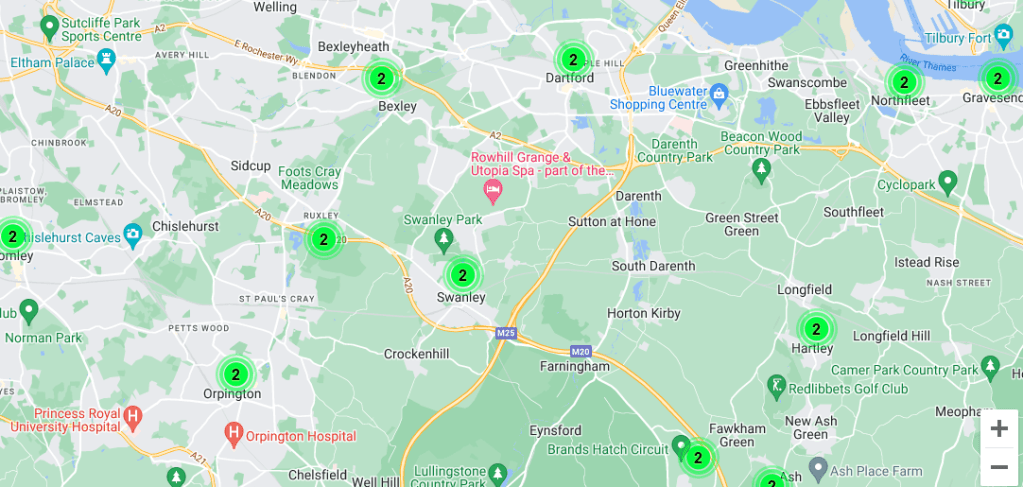

I live in a semi-rural area away from busy roads. Whilst there is some traffic, most of the pollution inside my home is generated inside my home. Some external pollutants will find their way indoors (possibly by going up my chimney and back into the house when a door or window was opened), but local air outdoor quality at the time was very good – it has been windy and wet, which means that pollutants are well dispersed.

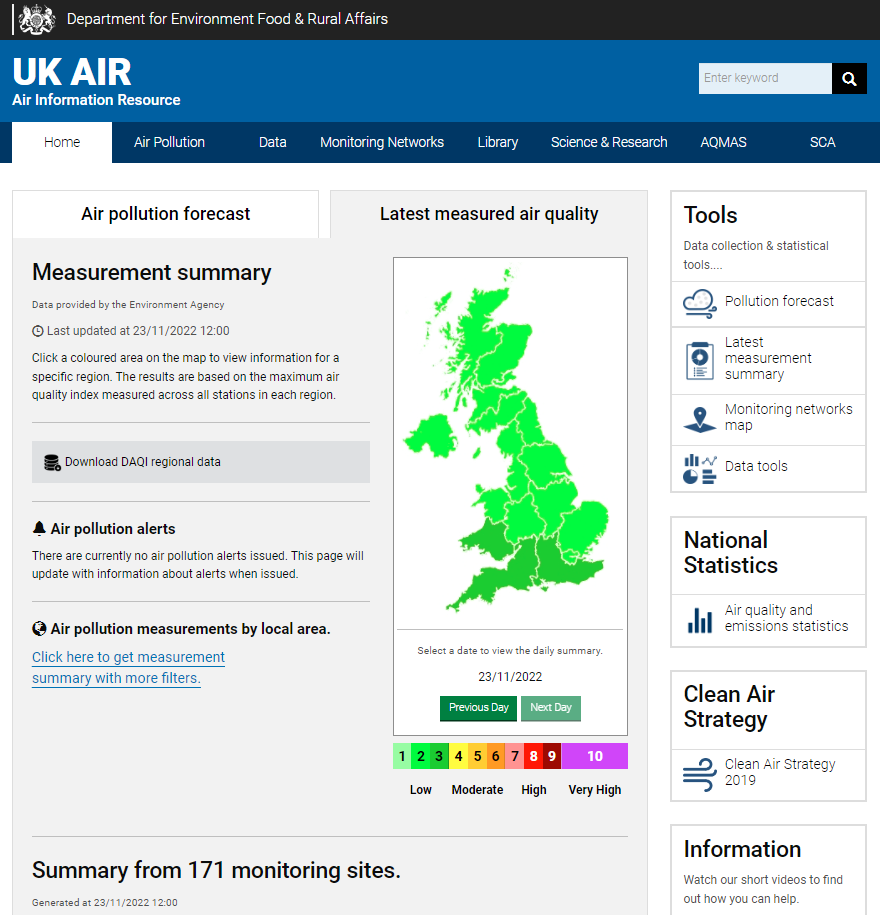

You can check local air quality measurements and forecasts on the UK Government’s UK Air Information Resource.

Knowledge is power. If you know what the air quality is like in the home (and outdoors), then you are in a good position to be able to do something about it.

Air purifiers, such as Vitesy’s new Eteria and their Natede products, are not only excellent at removing pollutants, but they are packed with top quality sensors, which can supply up-to-date information via the web to a smartphone. The screenshot here shows VOCs recorded on the Eteria air purifier that I have in my living room.

Once you know about the various air quality parameters, you can then do something about it – or let a smart device like Eteria do it for you.

As well as the suite of sensors in the device, there is an algorithm that tells it when to act, and with how much effort.

However, air purifiers can only operate over a small distance – unless you have room for a fridge-sized device, so there are other things you can do.

First, look at the data and see what is getting close to acceptable thresholds. If carbon dioxide is high, opening a window for a few minutes will be enough to refresh the indoor air. You might also be able to flush out some VOCs as well. However, if the outdoor air is cold and still, there is a risk that you might bring something nasty indoors.

The other thing you might be able to do is stop the activity that is causing the problem, or minimize the effect. If cooking is adding pollution, then use an extractor. If using a wood burner, then make sure that it is as efficient as possible, the flue is clean, the doors are closed and the wood is well seasoned.

With portable air purifiers, like Eteria, you can move the device closer to the source of the problem. The light-activated catalyst inside the machine can break down VOCs very quickly.

One thing to remember is that having information about indoor air quality should not be alarming.

Air quality monitors are completely dispassionate. They record and report on objective data and make no judgement about the activities that led to the data. High VOCs might be as a result of a room scenter, new perfume, a delicious meal or even a Christmas tree – the machine doesn’t know. However, if you do get an alert when you don’t have a reasonable explanation, you then have the option to start looking for the cause, which might be less benign.

Vitesy air purifiers (Eteria, Natede Smart and Natede Basic) are distributed in the UK to domestic and commercial customers by Nemesis Ltd

If you would like to learn more about indoor air quality or Vitesy’s excellent products, get in touch.

Last week, I visited the Workspace Design Show in London. It was a fascinating experience and there were lots of new, spangly products to help organizations create better, more effective workspaces, as well as some excellent talks and discussions.

It got me thinking about what it is that makes for a good office experience, and the characteristics of the best office environment that I have worked in.

I have been home-based for the last 14 years, but my various home offices over the years have not been the best offices that I’ve worked in.

That office was in an ageing building belonging to the head office of a multinational FTSE 100 plc where I worked for a little over 10 years in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

It wasn’t the condition of the building, that is for sure. It was built in the late 1940s, with additions from later decades. The heating was ancient, the network was flaky, the windows were tatty (although they were openable) and every so often, a vein of asbestos would be found, necessitating disruptive and costly removal.

However, there were many things to like about it.

First, almost everyone, no matter how junior, had there own office, or shared with one other person. They were adequately furnished, but every office was different, and every one reflected the person that used it – we were able to personalise our workspace considerably – plants, pictures from home, etc. I was allowed to choose the colour on the wall when the office was redecorated (after the asbestos had been removed), and I even brought in a coffee machine and a radio!

Another reason for it being a good place to work was its layout. Everyone tended to leave their doors open, meaning anyone walking along the corridor could pop their heads in and have a chat – usually work related, but not always. The building was very long and narrow, with toilets at opposite ends, and the post room / copier room also at a far end. This meant that several times a day, dozens of colleagues would walk past the office or pass each other in the corridor. It was a very social space, and it was a creative and productive space as well.

There were other features that made it a good, productive and creative environment, not least the nature of the work that was carried out there. As well as offices, there were laboratories and workshops. It had a collegiate atmosphere with a lot in common with academic institutions, despite it being a very commercial operation. However, there were two features that really stood out.

First, due to the nature of much of the work that was going on, especially in the laboratories, breaks were at fixed times and everyone went to the canteen at the same time – a really good time to talk to colleagues in different departments, and a really good place to exchange ideas and solve problems. A lot of lateral thinking went on in those coffee breaks and many of those conversations turned out to be serendipitous.

Secondly, there was the fact that the buildings were set in landscaped grounds. The site was a country house set in several acres of gardens, so absolutely atypical of 99% of workplaces. But those grounds gave everyone that worked there access to space to decompress, relax and reset – or just enjoy the greenery.

All that was achieved through a process of evolution and when I worked there, had developed over a period of roughly 50 years.

Of course, things change, and a new CEO decided that what the company really needed was a swanky open-plan floor in a posh, new office building in an expensive part Central London. The company crashed out of the FTSE 100 shortly afterwards, but I’m sure the two events weren’t entirely connected.

I recognise that my workplace was unusual, and had much more in common with an academic institution than the cut and thrust of a technology business or finance company. The building was owned by the company and its location was on the outskirts of a small town, not in a big city, but there are some lessons from that style of working that could be considered in modern metropolitan office buildings.

Having visited many office buildings in the last couple of years, most of which were barely a quarter-full, I have been struck by how organizations are desperately trying to create workplaces that will attract people to work in them – especially now that hybrid working patterns are taking hold and a lot of people would rather work from home.

The exhibitors at the show certainly had lots of ideas: zones for collaboration, pods for focused work and wellness rooms to recover from stress. Sofas and screens abounded, and of course, plants featured heavily (a good thing, of course). Every one of those solutions, however, lacked something really important – the ability for office workers to really realise something of their own identity. And as has been explained in older posts – identity realisation is the key to productivity. My friend Dr Craig Knight explains more here.

Whilst some degree of autonomy is available (the choice to work in a zone, pod or hot desk, for example), there is very limited ability to personalize individual workspaces. Despite huge budgets to create comfortable, ergonomic and efficient workspaces, and the provision of many amenities, such as high quality catering and recreation spaces, the new office building still remains far removed from the home environment where you can arrange your working environment to suit you.

Is it possible to recreate the style of office working that I experienced 25 years ago in a modern office building?

I don’t know. It would require people like HR managers and brand managers to relax a bit, and it might mean a different approach to space management, or even the architecture of office buildings.

Of course, my personal experience of what made for a good environment is just that – my own, personal experience. What worked for me might not work for anyone else at all, and the current design and management of workspaces might actually be the best possible way – feel free to comment.

The golf course meeting is a bit of a cliche. Executives in silly trousers getting together to hit little balls with clubs whilst at the same time sealing deals or hatching cunning business plans.

Such meetings were usually pretty exclusionary and often served to massage egos and provide tremendous opportunities for flattery and sycophancy. These days, they probably don’t occur as often.

However, aside from what passes as sport, there are probably some sound reasons why holding important meetings outdoors in a vast open green space is a good idea.

Most important business decisions are made during meetings behind closed doors. Meeting rooms – occupied by several people all concentrating hard on presentations and spreadsheets – may be private, but they might also be making it hard to think clearly.

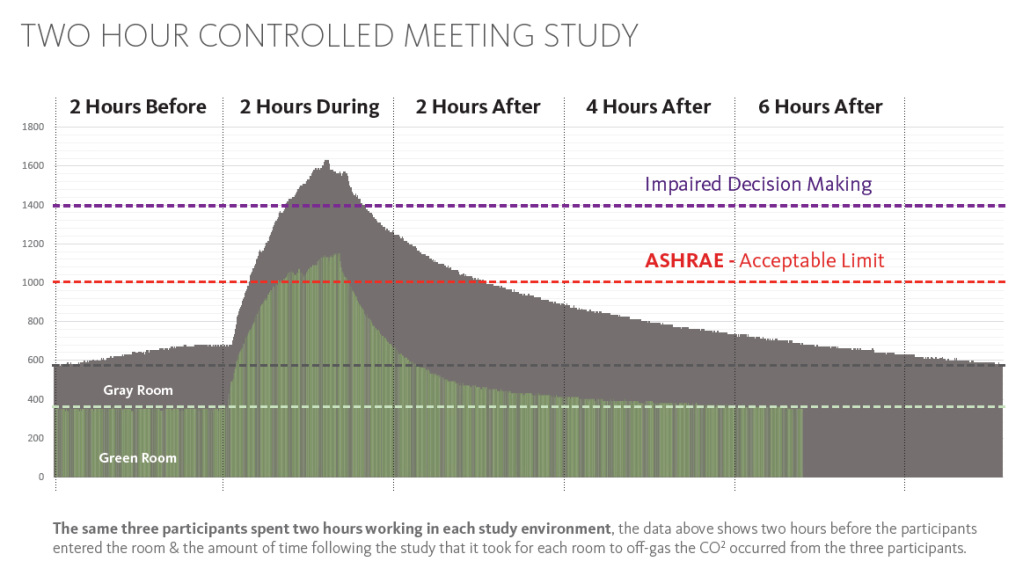

At ground level, carbon dioxide concentration in the air is approximately 400 ppm. When carbon dioxide concentrations rise to about 1,000 ppm, humans start feeling a little drowsy, and when they rise above 1,400 ppm our cognitive abilities start to decline – we find it harder to concentrate and make quick, rational decisions. A study carried out at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the USA showed that “On nine scales of decision-making performance, test subjects showed significant reductions on six of the scales at CO2 levels of 1,000 parts per million (ppm) and large reductions on seven of the scales at 2,500 ppm. The most dramatic declines in performance, in which subjects were rated as ‘dysfunctional,’ were for taking initiative and thinking strategically.”

So, what’s the problem? 1,400 ppm is over three times the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere – is it really possible to get to those levels?

The answer is yes, and it doesn’t take too long for a few breathing adults in a confined space to manage it.

Back in 2016, Gensler carried out a study in two identical meeting rooms (one of which was fitted with a small green wall) – a floor area of 21 square metres each, so about 50 cubic metres in volume. Three people working in those spaces, doing ordinary office tasks were able to elevate carbon dioxide levels to well over 1,400 ppm in a matter of minutes in the unplanted room (in the planted room, carbon dioxide exceeded 1,000 ppm, but reduced quite quickly – possibly as a result of the plants beginning to photosynthesize).

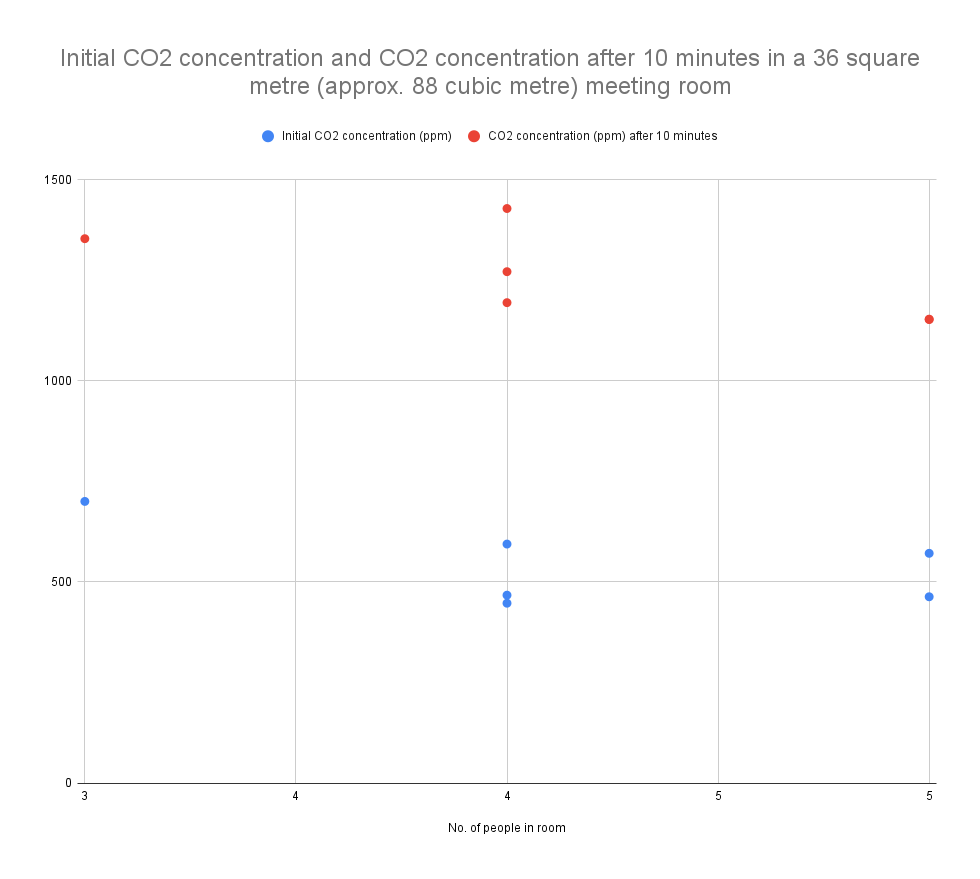

I carried out my own studies in a meeting room that had a floor area of 35 square metres (volume of just under 90 cubic metres), and it was possible for groups of only three or four to increase carbon dioxide concentrations to almost 1,500 ppm in 10 minutes, and that was in an office in an old building which wasn’t especially airtight.

As well as having an impact on cognitive ability and fatigue, high levels of carbon dioxide in a room are usually associated with other symptoms of discomfort, such as a feeling of stuffiness. This may have something to do with an increase in humidity and a rise in temperature that can also happen in confined spaces. Interestingly, some new research has shown a relationship between high levels of carbon dioxide and humidity with the transmissibility of airborne viruses – this is probably related to ventilation rates and is one of the reasons that carbon dioxide monitors are used to determine whether windows should be opened in school classrooms.

Holding meetings outdoors means that, as well as being exposed to fresher air, you are also exposed to the other sensory stimuli found in nature, and as discussed before, coherent sensory stimulation is one of the key components of biophilia.

Business meetings don’t have to take place on golf courses: a local park or woodland would do the job just as well. Imagine how much more productive businesses would be if they allowed the minds behind the business to work more effectively.

Lots of people are selling products that are supposed to improve indoor air quality. They may be air purifiers, filter systems, complex green walls or even pot plants. Many claims are made, but how do you know whether the systems you are buying are doing what you need them to do? This is where air quality monitoring comes into its own.

(By the way – I’m not trying to sell you an indoor air quality monitor, or any form of air purifier. However, I can help your business set up an IAQ monitoring project and even help you on your way to gaining a RESET certification for your buildings, which will also help you with WELL and Fitwel certifications – please get in touch if you want to know more).

Good indoor air quality is often thought of subjectively. Human perception of good air quality is difficult as our senses evolved to deal with environments that were unpolluted. As long as we could detect smoke, which suggested an immediate threat (or, conversely, the possibility of a cooked meal and convivial company), air quality was not much of a concern to our plains-dwelling ancestors.

Inside buildings, we often only notice an issue with air quality when it directly affects our comfort. We might describe the air as heavy, fusty, stale or stuffy. Stuffiness (often as a result of elevated carbon dioxide from our exhalation, combined with warm temperatures and high humidity) can be alleviated by opening a window. Carbon dioxide (and airborne viruses, such as Covid-19) inside the building is diluted by bringing outside air in, and humidity and temperature might also be made more comfortable. This improvement to our comfort, achieved by a perceived improvement to indoor air quality, is not the whole story.

Opening the windows might risk exposure to other harms that are not readily detected by human senses. Fine particulates, volatile organic compounds or various oxides of nitrogen or sulphur are not usually detectable by human senses, so how do we know whether they are present?

Only by using calibrated IAQ monitors that measure, record and report key parameters of air quality can you then set out to manage air quality and reassure the users of the building that their safety and comfort is being looked after.

Without data from air monitoring, any management of indoor air quality is pretty-much based on guesswork, which is inadequate for the proper management of risk in a building.

My new white paper explains how and why organizations should develop an indoor air quality monitoring and management programme, which you can download here.

Recently, I encountered a post on LinkedIn that made me a little cross. It was a post about the benefits of moss walls.

I like moss walls. They are a great way to add greenery to a space where live plants can’t thrive and they can be made into the most fabulous designs. Indeed the moss wall illustrated in the post was fantastic. The poster then started to make some claims. They started out OK, and if the author had stopped at a certain point, then everything would have been fine: a great moss wall, well illustrated, and a fantastic addition to any space.

Unfortunately, the poster then managed to conflate some research that he might have read about the impact that live moss has on improving air quality. I’ve read some of that research and it seems pretty sound to me, and I have been watching the development of live moss walls with interest – this product, for example, looks amazing.

However, it wasn’t a live moss wall that was being shown, it was a preserved moss wall. This is actually made with preserved lichens – a different type of organism altogether – and something that, when preserved and stuck to a wooden board, would stretch the definition of ‘alive’ to breaking point.

A little bit of sense checking with a technical person would have prevented this mistake and could have allowed the post author to create an article that wasn’t spoiled by a claim that is easily challenged.

It frustrates me when the marketing of good products and services is spoiled by over-exaggerated claims. It annoys me when marketing people put down people with technical knowledge because they have the temerity to point out that a claim might not be terribly robust or might be open to criticism. It really struck home once when a marketing team I was working with were desperately trying to put together a set of questions for a survey. In my naivety, I assumed that they were seeking objective data upon which to build a campaign and a message based on those data. This wasn’t the case. The exercise was to collect survey responses that would appear to validate the claims that they had already decided to make, and they were trying work out how to frame the questions to generate the answers they wanted to back up the claim. I was told that I needed to think like a marketer – was that an admission that marketing isn’t necessarily about truth?

Over the last several years, I have written articles and blog posts to support the marketing efforts of employers and clients. I think that I’m reasonably good at it. The reason that I think I’m quite good at it is because I write about what I know, have researched and am confident is true. Objectivity and reliance on evidence are crucial. I champion evidence-based design, solutions and propositions.

If you are an interior landscaper or in a related industry, and would like me to help you write (or sense check) marketing copy that is backed by evidence, science, research and over a quarter century of technical expertise in the industry, then please get in touch.

E-mail kenneth@purposefulplaces.co.uk or telephone +44 (0) 7543 500729

A lot of indoor plant sellers will tell you that indoor plants will purify the air. Sometimes, they refer to experiments carried out by NASA (40-odd years ago) to prove the point. However, careful analysis of some of these claims shows that the claims are often exaggerated, or taken out of context.

That doesn’t mean that plants have no impact on indoor air quality – they can. So, how can you get the most of plants’ abilities to affect the indoor environment? I can’t promise miracles, however.

In the early 1980s, NASA was investigating the ways that astronauts could maintain their environments whilst on long-term missions. The reaction of photosynthesis is a way of producing fresh oxygen for the astronauts to breathe, and some plants are good at removing other pollutants from the air and water.

The idea was that by having completely sealed living environments, humans and plants could live in complete balance. Coupling this with optimal growing conditions for vast amounts of greenery, the resources needed for a long-term mission could be reduced. This was only a few years after the last manned landing on the moon. Early space stations (Skylab and Mir – the forerunners of the International Space Station) had been launched and were being lived in for months at a time. This research clearly became very important.

The results of the experiments showed that some plants were especially good at removing pollutants such as some volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Some of these are quite unpleasant and are associated with harmful indoor air quality. These plants have become quite well known and are often referred to as the NASA list of air cleaning plants.

In 1984, the World Health Organization gave a name to a recently discovered phenomenon. People were feeling ill in modern buildings, and analysis of the environments in some of these buildings identified a number of VOCs as being likely causes of the problem. That problem became known as Sick Building Syndrome, and a great deal of effort was expended trying to identify the building components most responsible for the release of these chemicals into the air inside buildings.

It didn’t take long for someone to notice that a lot of the VOCs identified as being associated with sick building syndrome were those that some plants seemed to be good at removing. Indeed, one of the scientists involved with the original NASA experiments – Bill Wolverton – has since made a career writing about how houseplants can create fresh air.

Thinking back to the original NASA experiments, you will notice that they were carried out with a specific purpose in mind. The plants were grown under conditions that made them actively grow – their metabolism was optimized by controlling the environment with high light levels, good humidity, warm temperatures and precise levels of plant nutrients. There were also vast numbers of plants in the growth chambers.

If you ever visit the hot houses at a botanic garden, such as Kew or the Eden Project, you will experience exactly the type of environment the plants experienced in the NASA experiments. The air inside those spaces is uplifting, fresh and life-supporting. The difficulty lies in recreating those conditions in homes and offices.

Fortunately, since the early 1980s, the use of products in buildings associated with sick building syndrome has been significantly reduced. Most homes and offices are not full of nasty VOCs. However, there are some pollutants that have the potential to cause harm, or at least discomfort.

There are many sources of VOCs in houses. In fact, almost everything you can smell is a VOC of one type or another. Paints and new furnishings often release some compounds, but more mundane products are the biggest source: cleaning products, cosmetics and toiletries. Cooking, too, also produces types of VOC, as does opening a bottle of wine or mixing a cocktail. Most of these VOCs are harmless, although some can be irritating. Other VOCs are actually the result of human physiology. When you breathe out, there will be some VOCs on your breath as well as carbon dioxide and water – these are just the products of digestion and metabolism.

More worryingly are the VOCs that can enter the house from outside. Vehicle emissions, agricultural and industrial activities all contribute to VOCs in the atmosphere that will find their way indoors.

A more pernicious threat to human health comes from ultra-fine particulate matter, usually produced as a result of combustion. These are often classified as PM10 (particles smaller than 10 μm in diameter) and PM2.5 (particles smaller than 2.5 μm in diameter). These particles can be breathed deeply into the respiratory system, where they remain. Fine particulates come from vehicle exhausts, inefficient combustion of gases and even cooking.

Larger particulates, such as dust, can irritate the respiratory system and contribute to asthma and allergies. These are either produced inside buildings (and are usually composed of dead skin cells and pet dander), or can be blown indoors through doors and windows (such as fine dust from roads and fields or construction, or pollen from trees and grass). Since most homes are not airtight (and most people wouldn’t want them to be – opening a window is a great way to refresh the air and create cooling breezes indoors), there is little that can be done to prevent dust from getting in from the outdoors. Remember, also, that good ventilation is recommended as a way of reducing the risk of Covid.

The atmosphere is composed of approximately 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, 0.9% argon and 0.1% of all other gases (including 0.04% carbon dioxide).

About 80% of the entire atmosphere is within 15km (10 miles) of the earth’s surface (which is only 0.2% of the earth’s diameter) – a fragile and wafer-thin envelope upon which all life depends.

Elevated levels of carbon dioxide are more of a problem in offices than in homes. Small meeting rooms with lots of people, will result in CO2 levels rising fast and getting to concentrations high enough to cause drowsiness and impair cognitive function – just one reason why outdoor meetings might make for better business decisions. In the home, this is less of a problem, although in the winter, when everyone is indoors and windows remain firmly shut, CO2 levels might rise above comfortable levels.

Most homes cannot house enough houseplants to actively purify the air. They also cannot provide the necessary conditions for houseplants to be physiologically active. An environment that could replicate the effects found in laboratory experiments would be extremely uncomfortable for people to live in.

However, there are ways to use plants indoors to improve air quality, and some plants are better than others at doing this.

The key is to match the plants well to their environment. The more closely matched they are, the more physiologically active they will be, and that is when the effects will be greatest.

When you search for indoor plants online (whether for home or office), you will often see that retailers often include details about the conditions that they do best under. If you choose plants that suit the different conditions found in the various spaces in your home or office, then you are more likely to notice an effect.

First, the bacteria in the soil that live amongst the roots are able to break down some VOCs, and convert them into substances useful to the plants. This is an entirely natural phenomenon, although only relatively recently properly understood in horticulture. Plants with healthy roots and good soil will have the biggest impact, and those that are the fastest growing will also be the most effective.

Second, plants that are actively photosynthesizing will be removing some carbon dioxide from the air. Plants that originate in dark tropical conditions (such as rainforest floors) are able to photosynthesize extremely efficiently – they have evolved ways of making photosynthesis work even in very low light conditions, so that means more carbon dioxide is used by the plants.

It must be emphasized that the benefits to air quality are due to carbon dioxide removal, not increasing oxygen. Why?

The simple equation for photosynthesis shows that for every molecule of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere, a molecule of oxygen is added. So, in an office where the concentration of carbon dioxide might be, say, 600ppm, removing 100ppm is a massive reduction (about 17%) and will have quite an impact on the way you feel. However, at best, you will only be adding 100 ppm to the oxygen in the same space. As there is already roughly 210,000 ppm of oxygen in the atmosphere, adding an extra 100ppm to that is an increase of less than 0.05% – not noticeable at all. Actually, you get even that much back as the plants also need some of that oxygen for aspects of their metabolism.

Third, plants with hairy or slightly sticky leaves are able to trap particulates on the leaf surfaces, including fine particulates. In fact, plants such as ivy and Cotoneaster are used outdoors to mitigate the effects of pollution in urban areas. Some indoor plants can do that too (although they will need to be cleaned – there is no rain indoors to wash that pollution away). In fact, research carried out at Washington State University some years back showed that many different types of foliage plant attracted dust to their leaf surfaces – possibly as a result of an electrostatic effect – so almost any leafy plant will be useful.

Plants that are adapted to low light conditions will be the best to improve indoor air quality. They are especially effective in reducing VOCs and carbon dioxide. Plants in the aroid family, such as Spathiphyllum, Philodendron species, Aglaonema species or Monstera species will be good, as will other jungle-floor plants such as Calathea species, Ctenanthe and even small palms, such as Dypsis lutescens.

If light levels are slightly higher, Dracaena species have been shown to be effective at reducing levels of carbon dioxide. Experiments carried out in Australia by Margaret Burchett, Fraser Torpy and colleagues, in real office conditions, have shown that relatively few plants are needed to have a measurable effect).

Plants such as Ficus benjamina and varieties of ivy (Hedera helix) and some ferns that do well indoors are good at removing particulates.

Over recent years, the plant/microbe interactions in the soil have led to a number of innovations that use plants to actively clean the air. These systems were originally designed for large commercial spaces, but domestic-scale systems are becoming available.

In commercial buildings, green walls can have a dramatic effect on indoor air quality – especially when set up with good lighting systems. This is because green walls are set up with lighting systems, proper irrigation and, of course, hundreds of plants – all of which are physiologically active.

In the home, small green walls can now be purchased for relatively low cost, and can be installed by a competent DIYer. Not only do they take up little in the way of floor space, the large volume of compact plants in a good root environment means that they are going to be very effective – especially if you invest in some plant lights to illuminate them (and these are also getting much cheaper).

More recently, active air systems have been developed that use fans to pass air through the foliage and the roots to increase the size of the effect. Domestic-scale active air green walls are being developed and table-top systems, such as Vitesy’s Natede planter, are now already on the market.

Disclosure note: the author has commercial relationships with both foli8 and Vitesy. The author acknowledges their ownership of the copyright of their images in this article. The author is happy to recommend both companies. Their products and services are genuinely excellent.

I recently came across an interesting video, via a post on LinkedIn, on YouTube that explained, with the aid of Nerf guns of all things, how room acoustics could be modified by using different shaped acoustic panels.

The explanation is simple and very elegantly delivered. It also reminded me of some research carried out in the mid 1990s by Dr Peter Costa at Southbank University in London. His research looked at how interior plants can be effective at modifying room acoustics and make loud places quieter.

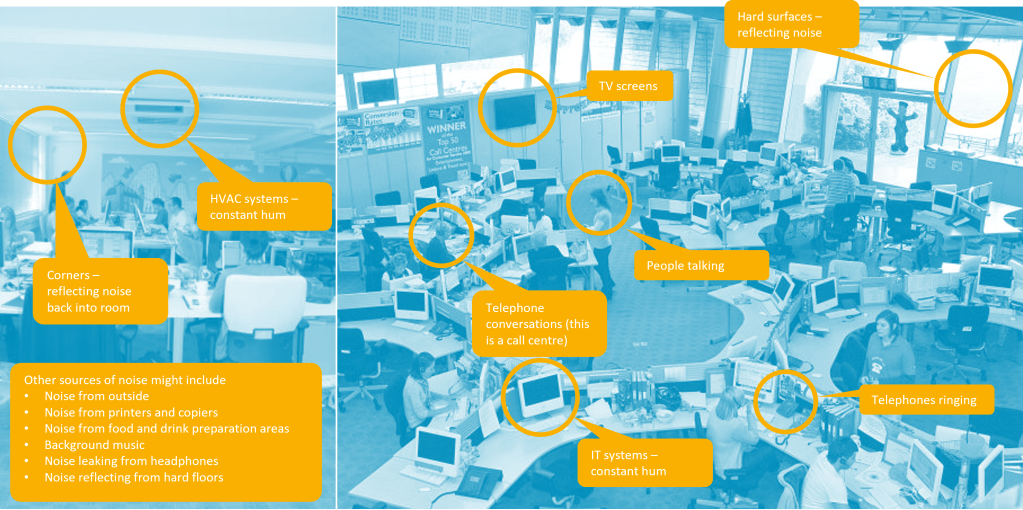

Noise, especially in offices, can be very distracting and can even cause stress. Mental discomfort, as well as being distracted from the task at hand, can make work unnecessarily tiresome and unproductive.

As people start heading back to the office, they may rediscover the nuisance of noise that might have been missing when working at home. Most homes are actually quite quiet (apart from the noises of children, domestic appliances and pets), and this is because of the amount of soft furnishings, fabrics and carpets that are commonly found.

The office, however, is different. Large, open plan spaces with hard surfaces and lots of right angles can be very noisy places. Sound is reflected all over the place and often not well absorbed. Sometimes you can find yourself tuning into a conversation from several desks away just because you happen to be in the path of the sound that is being bounced around the place.

There are very many excellent manufactured acoustic products that can minimize the effects of distracting noise in such places, ranging from fantastically sophisticated computer-controlled sound masking systems, using arrays of microphones and speakers, to simpler (yet still highly effective) products such as acoustic panels that can be placed in just the right places to deaden the noise.

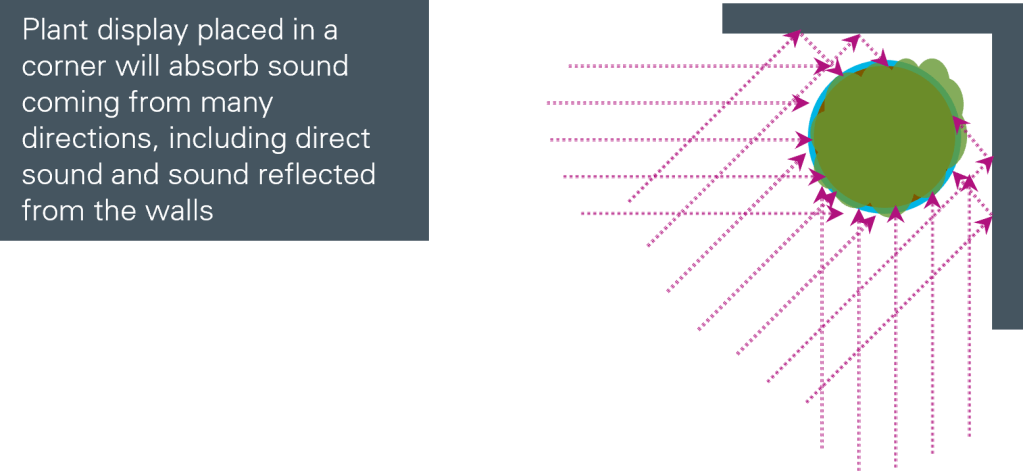

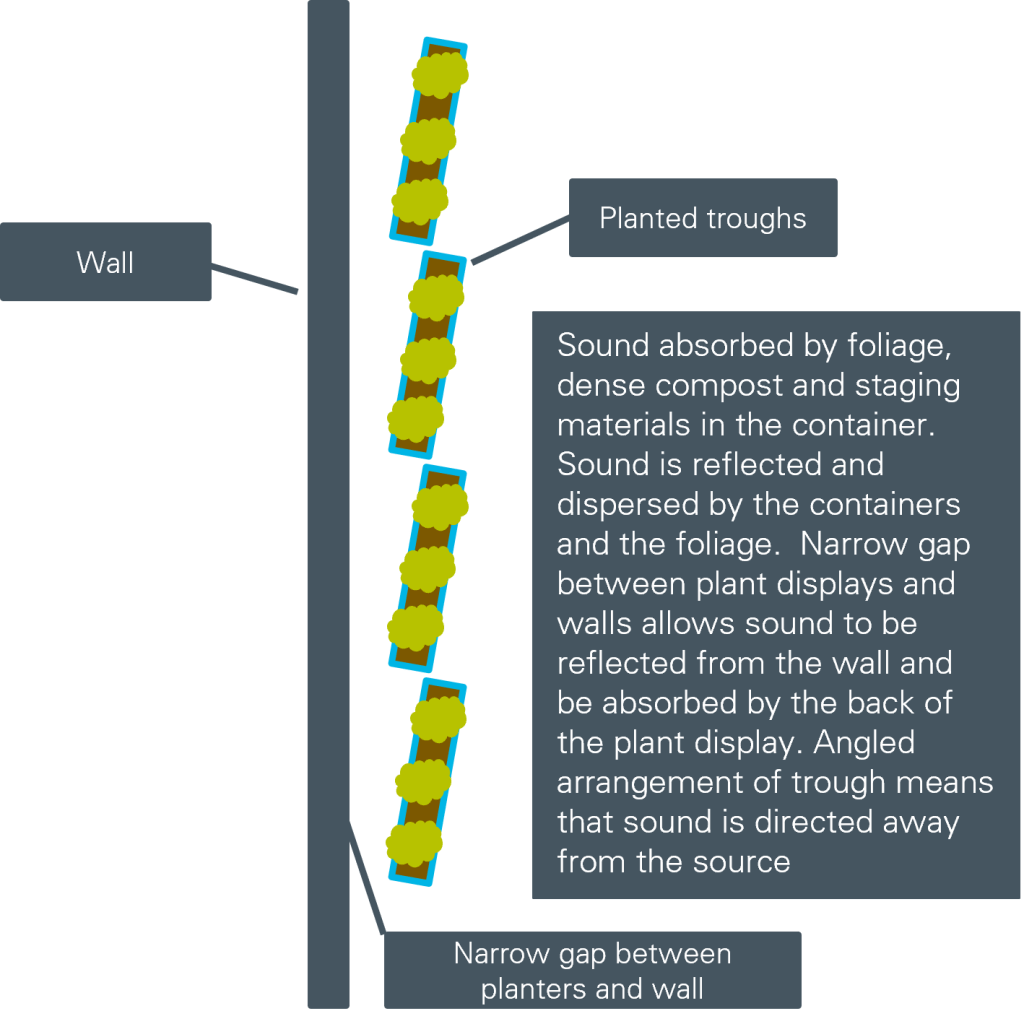

Looking again at the video, the key point is that by introducing shapes that disrupt the path of soundwaves as well as absorbing them, is a very effective way of reducing noise. This is where plants can make a useful (and very cost-effective) impact.

Plants are very irregular in shape. Their leaves point in different directions, are often textured, and foliage comes in all sorts of shapes and sizes. Mix up a variety of plant types and you will have surfaces scattering soundwaves all over the place.

Plants reduce noise by either absorbing sound or by breaking up the sound and scattering it through diffraction and reflection.

Plants alter room acoustics by reducing the reverberation time. Plants work better in acoustically live spaces, such as those that have hard surfaces like marble walls, exposed concrete and stone floors.

At lower frequencies plants may diffract and reflect sound. This is because the leaf size is small by comparison to the noise wavelength. Plants with lots of small leaves are useful as they scatter and diffuse sound. At higher frequencies the leaves may reflect sound towards other surfaces that may then absorb the noise.

By placing plants around a space where noise reflections are most likely to cause problems, you can achieve some meaningful improvements.

Green walls and moss walls have especially good acoustic properties. Green walls, as well as having a mass of dense foliage, are often mounted on panels made from products such as rockwool or dense foam plastics, both of which have excellent sound absorbing properties in their own right.

Moss walls are an excellent choice where a live plant green wall is not practical. The shape of moss deflects sound, whilst the texture of soft moss absorbs sound. Mounting materials also have some acoustic properties and, as they cover a large surface area, they absorb sound at different heights and from all directions.

As discussed earlier, noise levels in a large space are often not uniform. There are multiple noise sources, and the sound from any particular noise source can be magnified or focused some way from its origin due to the layout of the space. Sound might be reflected in one direction and blocked from going elsewhere. A distracting noise might be perceived some distance from its source. Sometimes the only way to be sure of where noise is coming from is to take some objective measurements with a noise meter and map where the noise ‘hotspots’ are found.

Measure the noise levels all around space, ideally when noise levels are typical for the location (e.g. during normal working hours for offices). You can create a map of the noise levels on a floor plan of the space by noting where noise levels are especially high or low. Then, try and identify the sources of the noise as well as where the noise is loudest (as discussed earlier – that isn’t necessarily the same place.

Noise meters are relatively inexpensive, and there are some quite useful apps for smartphones too that can be quite accurate (and are certainly capable enough to be able to measure relative differences in noise from place to place).

Once you have a map of noise levels and sound sources, then you can think about where vegetation will have its greatest impact.

As well as being excellent noise management tools, don’t forget that plants in buildings have a multitude of other benefits, not least their ability to improve wellbeing (and workplace effectiveness) when used as part of biophilic design.

For more information about how plants can make buildings better places to be, please get in touch. I can help building managers with your properties, or interior designers and interior landscapers seeking to add evidence-based value to your designs.

A few weeks ago, I completed my training and passed an exam to become a RESET Accredited Professional (AP) – one of approximately 500 around the world, and one of 51 offering services in the UK.

RESET is a data standard relating to the monitoring, recording and communication of indoor air quality. By being an accredited professional, I can now advise organizations and help them deploy an IAQ monitoring and reporting set-up that provides credible and independently-verifiable data on several key IAQ parameters, which can then be used to inform decisions on what IAQ solutions to deploy.

All too often, IAQ products and services are offered without sufficient evidence to demonstrate efficacy, or even need. Sometimes, some quite outlandish claims are made and impressive statistics are quoted that might be completely irrelevant to the context of the space concerned (interior landscapers – I’m looking at you. You can’t keep banging on about so-called NASA research on using plants to improve air quality if you don’t know how to measure it).

If you don’t know where to place an air monitor, how to interpret its data or even whether the monitor is accurate, then how can you be sure that your interventions to improve air quality are working? This is where a data standard is really useful.

The RESET approach is not a design standard – it doesn’t tell you what you must put in your buildings to improve air quality. RESET is a data standard. This means that if your organization is RESET certified, then you (and the users of your building) can be sure that the monitors you use measure the key IAQ parameters correctly (carbon dioxide, VOCs, temperature, humidity and fine particulates), and that the data provided by those monitors is handled, recorded and reported securely and impartially.

RESET also requires that IAQ data is made available in real time to the end users of the building (not just the building manager). This empowers users (e.g. office workers) to hold employers to account for the health and safety of their environment and can even help people make their own decisions about adjusting the environment to be more comfortable and healthy.

For me, being a RESET AP allows me to offer genuinely evidence-based solutions to my clients. I know how to set up an IAQ monitoring system, and I can then apply my knowledge of indoor air quality to recommend the most appropriate solutions (or point my customers in the direction of someone who knows better than me).

RESET is aligned with WELL, Fitwel and the Living Building Challenge, so if you are pursuing one of those standards, having a RESET-certified project will allow you achieve the relevant prerequisites relating to IAQ monitoring and reporting.

Yesterday, the UK government announced that all remaining restrictions relating to Covid-19 are to be relaxed on July 19th. There will no longer be a requirement to work from home when possible (something that seems to have been gradually ignored by many organizations for weeks already) and schools can abandon bubbles and even mask wearing and social distancing.

To mitigate some of the effects of increasing infections and the removal of passive measures such as masks and distancing, better ventilation of buildings is encouraged.

One way to measure ventilation is by using a proxy measure of carbon dioxide concentration, and that is pretty easily achieved with IAQ monitors. Carbon dioxide concentration is a good proxy measurement for ventilation as the higher the levels of CO2, the fewer air changes are taking place. If CO2 levels are high, then increasing ventilation is a good option. Not only will it have an impact on virus transmission, but it will also improve cognitive ability and reduce the risk of drowsiness. High levels of CO2 are very much associated with poor productivity.

The easiest way to improve ventilation is to open some doors and windows. In most schools, that is the only way to do it – very few schools have complex HVAC systems that can adjust ventilation rates and still pass air through filters.

If you have an IAQ monitor that measures a range of parameters, such as particulates and VOCs as well as CO2, then as soon as you open a window, you might discover that other pollutants increase rapidly – and then what are you going to do? Balancing the health risks of the different contributors to poor IAQ is hard enough already, without the added complications of a nasty virus

Many schools, especially those in urban areas, as well as office buildings, are situated near busy roads and particulate pollution especially is known to be very damaging to respiratory health. Measurements of particulates near roads are sometimes way above safe limits and high concentrations of fine particulates can kill or seriously damage health.

So, here is the puzzle that has to be solved. Will opening windows to reduce the risk of ill health due to airborne viruses (such as Covid-19) cause a bigger impact on health by letting in a whole load of other pollutants, especially fine particulates?

There are, of course, some things that can be done to reduce the amount of particulates getting into buildings.

The first is to reduce them at source. In urban areas, the main source is traffic, especially traffic using internal combustion engines. The rapid increase in electric vehicles is certainly going to help, but it will take many years before they are off the roads completely, and the most polluting types of vehicle are the hardest, at the moment, to electrify (big goods vehicles).

Next, you can try and reduce the chances of those particulates getting inside a building with open windows. This is not going to be easy, but there are some effective measures, and they are mostly green.

Green walls, green screens, climbing and scrambling vegetation, trees and hedges are all capable of trapping large quantities of particulates on their foliage, and have an impact on urban heat islands too.

Trees, hedges and plants like ivy are actually quite cheap too, and they are self repairing. They also reduce noise and look good too.

In the short term, using ventilation to flush out viruses (along with excess CO2) is going to be better than leaving windows closed and minimizing the ingress of fine particulates, but that is not a viable long term solution. Ideally, we should always have good ventilation to flush out viruses (it would be a good idea to use ventilation against all respiratory viruses, not just Covid-19), but if that is the case, we must do more to prevent other pollutants getting inside buildings. Vegetation is going to help a lot, but removing the source of those pollutants has to be the ultimate goal.

I have seen a notable increase in the number of posts on platforms such as LinkedIn extolling the benefits of ambient scenting – the addition of a high quality fragrance to the air inside buildings to make them more appealing (this is not the same as the use of air fresheners, no matter how sophisticated, to mask malodours in settings such as washrooms).

This is actually a subject I know quite a lot about (I’ve had a bit of a love/hate relationship with the subject since about 2007), and I can certainly vouch for the effects that scenting has on mood and the perception of the qualities of a space.

Ambient scenting can be used to reinforce brand values, make a place appear more luxurious and has even been shown in some experiments to reduce anxiety in healthcare settings. Some smells are very good at increasing the perception of good air quality – think of those fragrances that smell especially clean, fresh and hygienic.

Ambient scenting also has a role to play in biophilic design – potentially a very big role. Our sense of smell is our most primitive and we often react to a smell before we are consciously aware of it. Scents redolent of nature, when combined with appropriate visual and textural stimuli certainly add an extra dimension to a space – when our senses are stimulated congruently, our surroundings make more sense to us.

The technology of scenting is highly sophisticated (far more complex than an aerosol can or a scented candle) and is often programmable and even web-connected. Furthermore, the actual amount of fragrance chemicals released into the environment is actually really tiny – just enough to be perceived (this is especially true of nebulising systems). Some systems are designed to scent whole buildings through the HVAC infrastructure, with the fragrance oils introduced directly into the air handling unit.

As well as spotting the increase in the number of posts about the benefits of scenting, I have also seen an increase in posts about air purifiers. This is clearly a hot topic. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, poor air quality was high on the agendas of public health officials and building managers. Poor indoor air quality is associated with symptoms related to sick building syndrome and can, at times, pose a risk to the health of building occupants.

The development of new building standards, such as RESET, and the incorporation of IAQ monitoring standards into schemes such as WELL has brought not only management of IAQ, but also the monitoring and reporting of IAQ to the fore.

This is a good thing, and a subject that I have touched upon before. New research has shown that an increasing number of people are expecting more transparent reporting of IAQ in offices, especially amongst those facing a return to regular office work as pandemic restrictions ease.

Air purifiers are interesting products as well. Different systems employ a variety of technologies to remove fine particulates and remove, or breakdown, volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

Unfortunately, as far as I know, none of these air purifiers is able to distinguish between harmful, or unwanted, VOCs and those that smell nice and which were put in the environment deliberately.

The issue that is puzzling me is that many of the companies promoting ambient scenting are also promoting air purifiers, and this strikes me as strange. What drives this corporate cognitive dissonance?

If a company is selling an air purification system, one would hope that their sales people are able to present the features and benefits with some degree of conviction and be able to explain how an air purifier works and what it does to the chemicals circulating in the air.

Likewise, a sales person selling a scenting service should be able to explain how adding more chemicals to the environment can improve the users’ experience of a building (a scenting machine is a product that is designed to actively put more chemicals – no matter how safe they might be – into the environment). I’m not trying to be confrontational here – buildings that smell nice can certainly make using that space more enjoyable. People use fragrances all the time in homes and, of course, on their bodies.

It is quite possible that in situations like these it is likely that the left hand is unaware of what the right hand is doing. The people selling air purifiers may not be the same people that are selling ambient scenting (even if they work for the same company).

Furthermore, the purchaser of the scenting system might not be the same person as the purchaser of an air purifier (even if they work the same customer). If it is the same purchaser, that person now has the burden of potentially making an uninformed choice: is it reasonable to expect a customer to know that the air purifier will eliminate, or at least reduce, the efficacy of their expensive ambient scenting system?

One mitigating argument is that scenting systems are supposed to be situated where air purifiers aren’t. If that principle was universally applied, then there might be no issue – and maybe that is the norm. But I am not convinced that is always the case, especially with an increase in sales of portable air purifiers. These, by their nature, are going to be moved around and quite possibly moved into spaces where there is a scenting system in place. It is also possible that the person specifying the air purifier is unaware of the the presence of the scenting system.

I think it is unlikely that companies are deliberately selling both services to be used in the same spaces. There might be a short-term gain by doing so – the customer is going to get through a lot more expensive fragrance than might otherwise have been the case – but I doubt it would take very long for them to spot the problem.

Being a benevolent sort of person, I suspect that the poor sales people flogging air purifiers and scenting systems might not be sufficiently aware of the other products and services offered by different parts of their company (although their marketing departments ought to be). And if they are unaware, it makes it harder for them to help their customers make informed choices. This is clearly an opportunity for some training to be given (and if you are one of those companies facing this dilemma and would like some training developed for your sales and/or marketing people on this matter – please get in touch and I might be able to help you).

If sales people are actually selling both types of product, especially to a purchaser that might be responsible for buying both types of product, then there is an even greater need for some education to ensure that they remain credible and really understand the needs of the customer.