When I started in the world of interior landscaping, many years ago, the plants were usually the last thing to go into a building. Unless there were some big planter beds and atriums where trees and large-scale planting would be planned, most plant displays were in standalone planters.

This meant that interior landscape sales and design specialists were often brought into a project very close to the end of the design process. Furniture was in place and the lighting was installed.

A designer would visit the location, measure the light precisely where the plants were to be positioned and (usually) order the right plants for the prevailing lighting conditions.

Things have changed. Plants seem to be struggling where once they thrived, and it may not be as a result of poor plant quality from the growers, or poor maintenance by the interior landscapers.

Indoor lighting has changed

On 17 November 2025, I was fortunate enough to attend the second International Biophilic Design Conference in London. It was a packed day with several standout presentations. One that struck me as important was given by Ulysse Dormoy on the subject of light.

Ulysse Dormoy’s presentation spoke mainly about the role of far red (FR) and near infrared (NIR) wavelengths and their impact on human health. These wavelengths are just beyond the visible spectrum, and are essential for human health. This energy penetrates soft tissue and drives the reactions that take take place in mitochondria – organelles in every living cell (plants as well as animals) that power life.

The modern built environment – especially office buildings – relies on highly efficient LED lighting to illuminate our spaces. Modern, energy-efficient LEDs used in offices are often optimized to peak in the blue spectrum and only a narrow band of red (which is difficult to achieve in LEDs without losing efficiency) – this is fine for vision.

However, LED lights are almost devoid of the NIR and Far-red components prevalent in both sunlight and older light sources, such as incandescent and fluorescent lamps. Couple this with the treatments applied to glazing to minimize excess heat getting into buildings from sunlight, then we have a problem that might affect human health.

For humans, the absence of NIR means the loss of a key input for mitochondrial health, called photobiomodulation (PBM). This may lead to impaired cellular energy management that is thought to be linked to accelerated aging and reduced healthy lifespan.

So what?

What has this to do with biophilic design and, from my specialist point of view, interior plants?

As far as light is concerned, interior landscapers are faced with two problems. The first is light measurement and knowing whether there is enough for plant health.

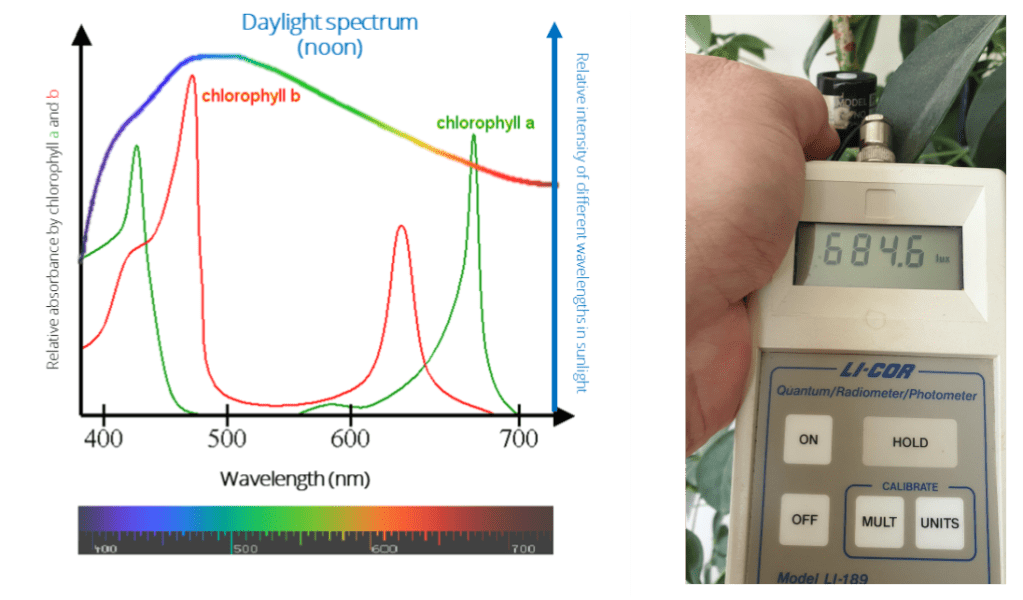

Conventionally, interior landscapers measure light using instruments that measure light intensity – measured in lux (or footcandles in North America). When interior lights were incandescent or fluorescent, then measuring light intensity was good enough. Indoor lights of this type produced wavelengths that were good for photosynthesis and there was a close enough correlation between light intensity and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) to mean that measuring light intensity was acceptable. Indeed, for decades, interior landscapers have relied on data sheets for indoor plants giving a range of light levels in lux (or footcandles) to aid specification.

PAR is a more accurate measure of useful light, and is measured as photosynthetic photon flux density – PPFD. With changes to lighting technology, PAR measurement might be the only way to understand what light is available to plants.

PAR is measured using much more expensive instruments than light intensity meters (shown above).

Unfortunately, no readily-available data exists for the PAR requirements of interior ornamental plants (although it does for salad crops, herbs and other plants grown in indoor farms). So even though the cost of PAR light meters is falling, without a reference point, interior landscapers don’t really know if the lighting in an office is going to be correct.

Who knows how many micromoles of photosynthetically active photons per square metre of leaf surface, per second, are needed for the optimal growth of a peace lily? I don’t, and I’m supposed to be an expert!

The second problem we face is akin to the human health angle.

Phytochromes

Just as humans need near infrared light for health, so do plants. Plants, like animals and fungi, have mitochondria. But they also rely on changes in the proportion of red and far red wavelengths to drive physiological processes that are not part of photosynthesis. These are the phytochrome reactions. The phytochrome system controls several growth and structural responses in plants, which govern the plant’s architecture and life cycle.

The phytochrome system functions as a molecular switch that allows the plant to perceive its light environment, particularly whether it is exposed to direct sun or under the shade of a competing canopy. This perception controls critical developmental processes.

Phytochromes are a family of chromoproteins that primarily absorb light in the 600–750 nm range. There are two interconvertible forms, distinguished by their maximum absorption peaks. The biologically inactive state, Pr (which stands for red-light absorbing form) is the default form synthesized in the dark. The biologically active state, Pfr, (which stands for Far-red light absorbing) is typically required to initiate developmental responses like germination or to inhibit stem elongation.

Red light (approximately 660 nm) is the activating signal. Exposure to red light quickly converts the inactive Pr form to the active Pfr form. A high proportion of Pfr signals full sunlight, triggering responses such as:

- the promotion of seed germination (in light-requiring seeds),

- inhibition of stem elongation (to maintain a compact, high-light-adapted form), and

- induction of flowering in some plant species.

Far-Red Light is the deactivating signal. Exposure to far-red light quickly converts the active Pfr form back to the inactive Pr form

The Red:Far-Red (R:FR) ratio and interior landscaping

As the sun tracks across the sky, and as seasons change, the ratio of red and far red light in the spectrum also changes. For optimal non-photosynthetic, light-driven processes, the wavelengths are not just about intensity, but about the ratio between the two main absorption peaks.

The Red:Far-Red (R:FR) ratio is the environmental parameter the phytochrome system is primarily able to sense, providing a crucial mechanism for shade avoidance. Direct Sunlight (High R:FR ratio of approximately 1.1–1.2) is natural, unfiltered light, which is rich in red light, leading to a high proportion of the active Pfr form. The plant perceives this as optimal growth conditions.

Canopy Shade (Low R:FR ratio of approximately 0.2–0.7) is found when light passes through a plant canopy. Chlorophyll strongly absorbs the red wavelengths (used for photosynthesis) but transmits or reflects the far-red wavelengths (which are less useful for energy fixation, but good for mitochondrial health in animals, such as humans). This skews the light spectrum toward far-red, rapidly converting Pfr back to Pr.

When the R:FR ratio drops (due to shade), the plant registers an urgent need to escape competition. This shift to the inactive Pr form triggers the shade avoidance syndrome, resulting in rapid stem elongation (etiolation), petiole extension, and suppression of branching. This isn’t an adaptation to low light, but an emergency response to get into brighter light.

The built environment challenge

As explained earlier, modern, high-efficiency LED lighting often lacks or is deficient in far-red and NIR wavelengths compared to older light sources. For indoor plants, a lack of the far-red signal (730 nm) can prevent the proper establishment of the shade-avoidance mechanism. If the R:FR ratio is skewed too high by narrow-spectrum red LEDs (a common energy-saving configuration), the plant may struggle because it loses the far-red component. This is critical for growth and development processes tied to phytochrome A, which is the primary photoreceptor for FR responses. Even though the plant is photosynthesizing, its morphological development is regulated by a spectral signal that does not fully mimic the complexity of the natural sun/shade environment. This leads to suboptimal plant architecture and poor acclimation.

Office buildings are dark places compared with the outside world. Even on a cloudy, winter day, daylight is several orders of magnitude brighter than that which is found indoors in even the most brightly-lit office. Our eyes adapt quickly to low light levels, but plants can’t.

The plant’s phytochrome system primarily detects the R:FR ratio to determine if it is under a competing canopy, not the overall photon density. In an indoor environment dominated by typical lighting (high in blue/green wavelengths, but little FR), if the light source is a standard LED or fluorescent lamp that has some red peaks but very little Far-Red, the R:FR ratio will be high (similar to direct sunlight). This results in a response suppression. The plant maintains a high level of the active Pfr form of phytochrome, signalling “full light.” This suppresses the shade avoidance syndrome (etiolation).

However, there is another problem.

Far-red light is not just a signalling mechanism.

It is also an efficiency booster for photosynthesis itself. This is called the The Emerson Effect. Essentially for indoor plants, by completely removing FR from the indoor light spectrum, modern LEDs seem to be reducing the overall efficiency of photosynthesis. This makes the plants less efficient at utilizing the even the low light quantities they do receive. This further exacerbates their struggle. Therefore, while the lack of FR prevents undesirable etiolation, it forces the plant into a compromise that prevents true low-light adaptation and limits the efficiency of its remaining photosynthetic processes.

The plant structurally maintains a compact, short-stemmed, sun-adapted form, but the actual photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) remains too low. The plant is tricked into behaving as if it is in high light when it is actually in low light. True, long-term low-light adaptation (shade adaptation) involves changes to the photosynthetic machinery, such as

- Increased chlorophyll density (producing more chlorophyll per unit area to maximize the capture of scarce photons),

- Thinner, larger Leaves that maximize the surface area for light interception and reducing the energy spent on thick, robust leaves.

This shade adaptation is a slow process and starts on a grower’s nursery and has meant, in the past, that indoor plants can cope with office lighting conditions.

However, a high R:FR ratio (due to lack of FR) actively inhibits these true shade-adaptation responses. The plant remains stunted but not acclimated. It is physiologically light-starved because its genetic programming, signalled by the high R:FR ratio, is telling it to stay structurally compact and save energy, making it struggle even more over time.

When incandescent and some fluorescent lights were used, the low light levels – which the plants could adapt to – they had the right R:FR ratio. Now, they don’t and indoor plants, which are well acclimated to low overall light levels, are struggling and not living as long.

4 thoughts on “Get the light right”